Chapter 8: DIAGRAM OF THE STUDY

OF THE MIND

| Contents | |

|---|---|

| Ch'eng Fu-hsin's Explanation of the Diagram | 160 |

| T'oegye's Comments | 162 | Commentary |

| On Reading the "Diagram" | 165 |

| The Human Mind and the Mind of the Tao | 166 |

| The Essence of Cultivating the Mind-and-Heart | 169 |

| The Placement of this Diagram | 171 |

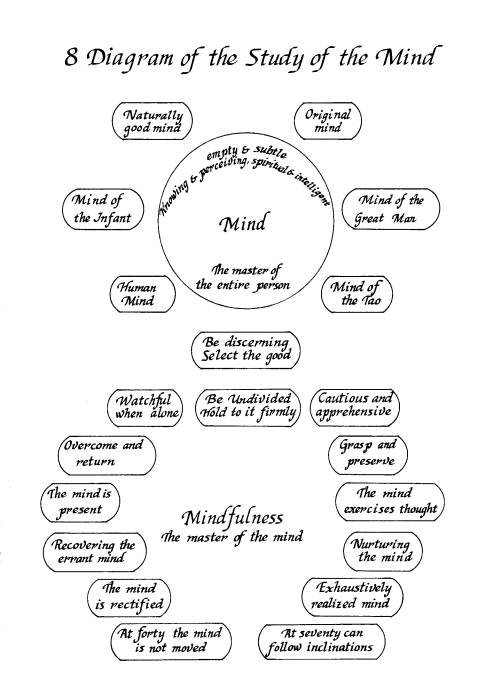

From his youth Chen Te-hsiu's Classic of the Mind-and-Heart1 was one of the most important and formative influences on T'oegye. In the supplemented and annotated edition that circulated widely in Korea and was used by T'oegye, the Hsin-ching fu-chu (Simgyŏng puju),2 this diagram and its explanatory text are inserted immediately before the first chapter with the following note: "This diagram of Mr. Ch'eng [Fu-hsin]3 exhausts the wonders of the study of the mind-and-heart, and what it discusses likewise suffices to manifest the essence of the study of the mind and heart.4 Thus it serves as both an introduction and summation to the Classic of the Mind-and-Heart. T'oegye, who remarks that he has always "loved this diagram,"5 uses it here in a similar fashion, making it an introduction to and summation of Neo-Confucian ascetical doctrine, the method of cultivating one's mind-and-heart, which is the central concern of the Classic.

In China the term "study of the mind-and-heart (hsin-hsüeh)" became, in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), a designation for the Lu-Wang school of thought, pointing to that school's emphasis on the direct cultivation of the innate goodness of the mind, in contrast to the Ch'eng-Chu school, which insisted that the investigation of principle is essential since understanding is analytically prior to practice. The Ch'eng-Chu school thus became characterized as "the study of principle."

This development has somewhat obscured the fact that the study of the mind-and-heart is likewise central in the Ch'eng-Chu school. Chen Te-hsiu's Classic of the Mind-and-Heart and Ch'eng Fu-hsin's "Diagram of the Study of the Mind-and-Heart" both witness the vigor with which

160 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

this aspect of Chu Hsi's teaching was developed during the Yiian dynasty (1279-1368).6 T'oegye's constant emphasis upon the centrality of mindfulness is a faithful reflection of Chu Hsi, but it is also an unmistakable reflection of the influence of Chen's Classic,which played such a central role in his early and middle years and formed his mind before he had the opportunity for his later immersion in Chu Hsi's own works.

Ch'eng Fu-hsin's Explanation of the Diagram7

Ch'eng Lin-yin [Fu-hsin] says: "The 'mind of the infant'8 is the `naturally good mind'9 before it has been disturbed by human desires; the `human mind'10 is the mind that has been awakened to desire. The `mind of the great man'11 is the `original mind'12 which is perfectly endowed with moral principle; the `mind of the Tao'13 is the mind that has been awakened to moral principle."

This does not mean that there are two kinds of mind; but since in fact man is produced through the material force that gives one physical form, no one can be without the "human mind"; and [at the same time] origination [as a human being] is from the nature, which is the Mandate [of Heaven], and this is what is referred to as the "mind of the Tao."

[The lower half of the diagram], from "be discerning and undivided, select [the good] and hold to it firmly,"14 on down, is concerned with the efforts to block [selfish] human desires and to preserve the principle of Heaven [which is our nature.] [On the left-hand side] from "watchful when alone,"15 on down are the efforts addressed to blocking [selfish] human desires. In this it is necessary to reach the stage described as "the mind is not moved";16 then "Wealth and high position will not be able to corrupt him, poverty and low estate will not be able to move him, and majesty and force will not be able to bend him."17 At

162 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

this stage one can see his tao has become lustrous and his virtue has been established.

[On the right-hand side], from "cautious and apprehensive,"18 on down are the efforts regarding preserving the principle of Heaven. In this it is necessary to reach the stage described as "can follow one's inclinations";19 then the mind will be identical with its substance and desires identical with function, and that substance is the Tao and that function is righteousness. One's speech will accord with the norm and [the actions] of one's person will accord with the proper standard. At this stage one can see he may "apprehend without exercising deliberate thought, hit upon what is right with no deliberate effort."20

In sum, the essence of applying one's efforts is nothing other than a matter of not departing from constant mindfulness, for the mind is the master of the entire person and mindfulness is the master of the mind. If one who pursues learning will but thoroughly master what is meant by "focusing on one thing without departing from it,"21 "being properly ordered and controlled, grave and quiet,"22 and "recollecting the mind and making it always awake and alert,"23 his practice will be utterly perfect and complete, and entering the condition of sagehood likewise will not be difficult.

T'oegye's Comments

Ch'eng Lin-yin collected together the terms in which the sages and wise men have discussed the study of the mind and made the above diagram of them. His categorically distinguishing and arranging them in corresponding pairs is complex but not tiresome, for by this means he shows that the system of the mind-and-heart in sage learning is likewise complex, and one must apply diligent effort to all these aspects.

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 163

[The lower half of the diagram] is arranged in an order that proceeds from the top to the bottom; it is meant as a schematic presentation [ of the process of self-cultivation] simply in terms of what is shallower and what more profound, what is less mature and what more mature. Since this is its approach, it does not mean to depict the stages and steps of the process in the temporal order of prior and posterior, as [does the Great Learning in speaking of] extending knowledge to the utmost, making the will sincere, rectifying the mind, and cultivating one's person.24

But someone25 might doubt: "Since you say it is a schematic arrangement, `recovering the errant mind'26 is the very first step in applying one's efforts, so it should not be placed after 'the mind is present.'"27

I would suggest that if one speaks of "recovering the lost mind" in the more shallow sense, it certainly comes as the very first step in applying one's efforts [to self-cultivation]; but if one speaks of it in a more profound and ultimate sense, if for even the slightest moment a single thought deviates a tiny bit, it also may be termed an "errant mind." Such was the case when Yen Hui was described as not being able to avoid deviating [from the perfect observance of humanity] after a period of three months.28 If one cannot entirely be without deviation, any deviance is a slip into an errant condition; when Yen Hui made the least mistake he could immediately recognize it, and having recognized it would not repeat it,29 and this also may be classed as "recovering the errant mind." Therefore the order of Ch'eng's diagram is as it is.

Mr. Ch'eng's courtesy name was Tzu-hsien, and he was from Hsin-an. He dwelt in retirement and did not take office; the correctness of his conduct was extremely perfect. From youth to old age he exhaustively studied the Classics and gained a profound understanding of them. He was the author of the Diagrams of the Sentences of the Four Books, in three kwŏn (chüan).

164 Diagram o f the Study o f the Mind

When Emperor Jen-tsung [r.1311-1320] of the Yüan dynasty, due to a special recommendation, summoned him and intended to employ him as an official, Tzu-hsien did not wish to comply. He was made a provincial erudite (hsiang-chün po-shih), but resigned his position and returned home. Such was the kind of man he was;30 how could he have failed to understand [concerning "recovering the errant mind"] and made a mistake!

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 165

Commentary

On Reading the Diagram

We have seen that one aspect of the investigation of principle is the patient play of the mind over the diversity of the authoritative sources, trying to see how each speaks with its own voice and exposes an aspect of the topic, while final insight comes through comprehending their interrelationship as multiple facets of a single whole. The diagrammatic form, so popular in Korea, is an instrument well suited to this approach. The object of diagrammatic schematization is not rapid and simplified learning but rather the structured presentation of a body of complex, interrelated material as an aid to sustained reflection. This is clear in T'oegye's advice on reading the upper part of this diagram:

One must see in it the kind of thing the mind is: in the midst of its undifferentiated integral substance it is divided up like this in accord with the ways it is manifested or the aspects one attends to. The various kinds of terminological headings are meant to make one who pursues learning base himself upon these terms and seek out their meaning and intent. If for a long time one mulls them over and savors the taste [of each] with a personal understanding, then all the principles will coalesce, and in this is found the integral substance of the mind. (A, 23.28a, p. 561, Letter to Cho Sagyŏng)

What T'oegye understands as the "meaning and intent" of the terms and their arrangement in the upper portion of the diagram is presented in the following passage:

The six types of mind arranged above, below, and to the right and left of the "mind" circle simply describe how there is a particular point to each of the ways the sages and wise men talk about the mind. It is like this: because of its fundamental (ponyŏn, pen-jan) goodness it is called the "naturally good mind"; because of its original possession (ponyu, pen-yu) of goodness it is

On Reading the Diagram

We have seen that one aspect of the investigation of principle is the patient play of the mind over the diversity of the authoritative sources, trying to see how each speaks with its own voice and exposes an aspect of the topic, while final insight comes through comprehending their interrelationship as multiple facets of a single whole. The diagrammatic form, so popular in Korea, is an instrument well suited to this approach. The object of diagrammatic schematization is not rapid and simplified learning but rather the structured presentation of a body of complex, interrelated material as an aid to sustained reflection. This is clear in T'oegye's advice on reading the upper part of this diagram:

One must see in it the kind of thing the mind is: in the midst of its undifferentiated integral substance it is divided up like this in accord with the ways it is manifested or the aspects one attends to. The various kinds of terminological headings are meant to make one who pursues learning base himself upon these terms and seek out their meaning and intent. If for a long time one mulls them over and savors the taste [of each] with a personal understanding, then all the principles will coalesce, and in this is found the integral substance of the mind. (A, 23.28a, p. 561, Letter to Cho Sagyŏng)

What T'oegye understands as the "meaning and intent" of the terms and their arrangement in the upper portion of the diagram is presented in the following passage:

The six types of mind arranged above, below, and to the right and left of the "mind" circle simply describe how there is a particular point to each of the ways the sages and wise men talk about the mind. It is like this: because of its fundamental (ponyŏn, pen-jan) goodness it is called the "naturally good mind"; because of its original possession (ponyu, pen-yu) of goodness it is

166 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

called the "original mind"; as being simple and without any artificiality, and nothing more, it is called the "mind of the infant"; as simple and without any artificiality and being able to comprehend all changes totally, it is called the "mind of the great man"; being produced through the psychophysical component it is called the "human mind"; and having its origin in the Mandate which constitutes the nature, it is called the "mind of the Tao."31 Since the "naturally good mind" and the "original mind" have very similar types of meaning they are placed in correlation to each other at the top on the left and right; the "mind of the infant" and "mind of the great man," and the "human mind" and the "mind of the Tao," because their fundamental terminology involves a mutual contrast, are arranged in pairs to the left and right of the middle and bottom respectively. (A, 14.35b, p. 378, Letter to Yi Sukhŏn)

The Human Mind and the Mind o f the Tao

Two of the pairs of terms regarding the mind in the upper half of the diagram come from Mencius, as well as six of the twelve items in the lower half of the diagram. This reflects his importance for the Neo-Confucian theory of the mind-and-heart, a topic which he discussed more than any other classical author. But the explication of this terminology also shows that his primary concern was to establish the fundamental goodness of human nature. Chang Tsai, some 1,300 years later, finally provided Confucians with a doctrine that could explicate an intrinsic source of aberrant tendencies within man without thereby vitiating the fundamental and vital fact of goodness at the core of human nature that Mencius was so concerned to defend: this was the doctrine of the physical nature. This development called for an authoritative classical source and terminology that would reflect not only the innate goodness, but also the problematic side of human dispositions. It was found in a passage in the Book of Documents: "The human mind is insecure, the mind of the Tao is subtle; be discerning, be undivided [One]. Hold fast the Mean!"32

This passage, as is evident in the diagram, became the keystone

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 167

of the understanding of the mind in the Ch'eng-Chu school: the "mind of the Tao" embodies the innate goodness of human nature spoken of by Mencius and enshrined philosophically in the doctrine that equates human nature with principle, while the "human mind" is taken as a manifestation of the physical nature, Chang Tsai's explication of evil.

The Classic of the Mind-and-Heart is a compendium of quotations. Not surprisingly, it begins with this passage on the mind of the Tao and the human mind, and this is immediately interpreted by a quotation from Chu Hsi:

The empty spirituality33 and consciousness of the mind-and-heart are one and undivided. But there is a difference between the human mind and the mind of the Tao since some aspects arise through the individuality [or selfishness] of the physical form while some originate in the rectitude of the Mandate that is the nature, and the consequent type of consciousness is not the same. Therefore the one is perilous and insecure and the other is wondrously subtle and difficult to perceive. Nevertheless, there is no one who does not have physical form, and so even the most wise cannot be without the human mind; likewise there is no one who does not possess this nature, and so even the stupidest person cannot be without the mind of the Tao. These two are mixed together within the mind-and-heart, and if one does not know how to control them the perilous will become even more perilous and the subtle will become even more subtle and in the end the impartiality of the principle of Heaven will not be able to overcome the selfishness of human desire. If one is discerning he will discriminate between these two and not let them get mixed. If one is undivided he will maintain the rectitude of the original mind and not become separated from it.34

This passage, which comes from Chu Hsi's introduction to the Doctrine of the Mean, is the most important single interpretation of the rather vague words of the Book of Documents. One notes that in spite of the affirmation of the fundamental goodness of human nature-the mind of the Tao-the tone is exceedingly reserved and highly aware of the weakness or moral peril which attends our psychophysical endowment, manifested as the human mind. DeBary has characterized this well as a moral "rigorism,"35 it is an uneasy partner with the more affirmative Mencian heritage.

168 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

It would be easy, from Chu Hsi's words above, to slip into an attitude that virtually equates the psychophysical endowment or "physical nature," and the "human mind," its manifestation, with selfishness (sa). However the observation that even the wisest, that is, the sage, also has a "human mind," is a warning that the equation cannot be that simple. T'oegye notes that the disciples of the Ch'eng brothers understood the "human mind" as selfishness, and that Chu Hsi at first followed them in this but later corrected it.36 He observes that sa may mean not "selfish," but "private," i.e., pertaining to the individuality of human existence, which is a consequence of physicality; it is in this sense that one should understand the "human mind."37 Thus he carefully distinguishes between equating the human mind with selfishness and saying that it is the basis from which one may easily slip into selfishness:

The human mind is the foundation of [selfish] human desires. Human desires are the flow of the human mind; they arise from the mind as physically conditioned. The sage likewise cannot but have [the human mind]; therefore one can only call it the human mind and cannot directly consider it as human desire. Nevertheless human desires in fact proceed from it; therefore I say it is the foundation of human desires. The mind ensnared by greed is the condition of the ordinary man who acts contrary to Heaven; therefore it is termed "human desire" and called something other than "human mind." This leads one to understand that such is not the original condition of the human mind; therefore I say it is the "flow" of the human mind. Thus the human mind is prior and human desires come later; the former is correct and the latter is evil.38 (A, 40.9b-10a, p. 897, Letter to Nephew [Yi] Yŏnggyo)

This careful analysis gives full recognition to the fundamental soundness of man, including his physicality and the desires that may appropriately follow from it. But it also recognizes the tendency for the fact of individuality to flow into the aberration of self-centeredness; the more turbid one's psychophysical endowment, the more entrapped one becomes in individuality and the less able one is to live by the community of principle.

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 169

The Essence o f Cultivating the Mind-and-Heart

The approach to the cultivation of the mind-and-heart is conceptualized in terms of the polarity of the mind of the Tao and the human mind. T'oegye sums it up as follows:

In general, although the study of the mind-and-heart is complex, one can sum up its essence as nothing other than blocking [self-centered] human desires and preserving the principle of Heaven, just these two and that is all . . . . All the matters that are involved in blocking human desires should be categorized on the side of the human mind, and all that pertain to preserving the principle of Heaven should be categorized on the side of the mind of the Tao . . . The intent of Ch'eng Lin-yin's "Diagram of the Study of the Mind-and-Heart" is truly like this. (A, 37.28b, p. 849, Letter to Yi P'yongsuk)

The subtlety of the mind of the Tao implies that it may easily be obscured, and the perilousness of the human mind signifies the ease with which it may slide into self-centeredness. Clearly this leads to a kind of moral rigorism. But the categorizing of moral self-cultivation is bipolar: something good to be preserved and nurtured, and something potentially negative to be guarded against and blocked off. As deBary has observed, this makes Neo-Confucian moralism something quite different from the more exclusively negative focus of western Puritanism. 39

The division of the stages of moral growth according to the mind of the Tao and the human mind basically separates the purely positive from that which implies a negativity to be brought under control. To complete the picture, it is further necessary to see cultivation in terms of the cultivation of the mind in its two states, before it is aroused (substance, the nature) and after it is aroused (function, the feelings). It was not possible to incorporate this dimension directly into the diagram, for both the mind of the Tao and the human mind are technically manifestations of the composition of the mind rather than actual components, and thus belong on the "after it is aroused" side. Nonetheless, there is a general symmetry between the diagram's distinction of preserving the principle of Heaven and blocking human

170 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

desires and cultivating the mind in its quiet and active states respectively: blocking human desires clearly belongs to the active state of the mind, while preserving principle looks to the quiet union of the mind with principle (nature, substance) and the undivided, consistent maintenance of this principle as the mind moves forth into activity. When viewed within this framework, one might further observe, what emerges as of critical importance is not so much either the quiet or the active states of the mind as such, but rather the point of interchange between the two, the subtle incipience (ki, chi) of activity in which lie the seeds of what is to follow.

From this perspective, then, one can understand why mindfulness assumes a central importance in this diagram. Equally applicable to the quiet and active states of the mind, it also presides over the transition and is in fact the essence of cultivating the mind-andheart. T'oegye says:

As for man's receiving the Mandate from Heaven, he is endowed with the principles of the four virtues, and that which is the master of his person is the mind. That which is stirred within by things and follows the subtle incipience (ki, chi) of good and evil as the function of the mind is the feelings and the intention. Therefore the superior man, when this mind is quiet, unfailingly preserves and nurtures it to maintain its substance; when the feelings and intentions issue forth, he unfailingly exercises self-reflection and discernment in order to rectify its function.

Nonetheless, the principle of this mind is so vast it cannot be concretely laid hold of, so boundless it cannot be limited. If there is not mindfulness to make it undivided, how will one be able to preserve its nature and establish its substance! The issuance of this mind is subtle, as difficult to discern as the most minute particle; it is insecure, as perilous as treading [the edge of] a deep pit. If there is not mindfulness to make it undivided, then again, how will one be able to rectify its subtle incipient activation (ki, chi) and perfect its function!

Therefore the superior man's way of learning is this: when the mind is not yet aroused, he unfailingly takes mindfulness as primary and applies himself to the preservation and nurture of the mind; when the mind has been aroused, he likewise unfailingly takes mindfulness as primary and applies himself to reflection and discernment. This is how mindfulness is the means

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 171

by which both the beginning and the end of learning is accomplished; it runs throughout both substance and function [i.e., quiescence and activity]. (Ch'ŏnmyŏng tosŏl, ch. 10, B, 8.20a-b, p. 144)

One notes the special importance here of the "subtle incipient activation" (ki, chi), the almost imperceptible arising of currents in the mind which grow into full-fledged forces of good and evil. The subtle incipient activation is logically schematized as the incipience of activation after quiescence, but in a more general sense there is also such incipience whenever our ever-changing context calls forth new feelings and reactions. The constant emphasis upon mindfulness, a calm, recollected, self-possessed state of mind, bespeaks a resolve to bring these subtle beginnings under conscious, discerning control. There is an inverse proportionality at work in this, for at this level evil is most easily blocked and controlled, but the highest and most demanding mental discipline is required to exercise discernment at such a subtle level. The general moral observation that "the human mind is perilous" is thus paired with an analysis of the genesis of mental conditions, and together these point to the rigorous kind of mentally oriented moral cultivation that may be summarized by the single expression, "constant mindfulness."

The Placement of this Diagram

In the original order of the Ten Diagrams, this chapter preceded the chapter on Chu Hsi's "Treatise on Jen." Yi I (Yulgok) wrote to T'oegye suggesting that their positions should be reversed, and T'oegye, observing that he had already been thinking about that, readily agreed.40 Unfortunately, neither letter mentions any reason for the desirability of such a change. Nonetheless, there is a difference made by the order that made it an object of concern for them, and it is appropriate to consider what that difference might be, even in the absence of direct evidence as to what T'oegye and Yulgok had in mind.

172 Diagram of the Study of the Mind

The sixth chapter describes the structure and constitution of the mind, and the present chapter introduces the correlative approach to self-cultivation. A chapter dealing with jen, the epitome of all virtue, might logically follow these as a depiction of the highest achievement in Confucian self-cultivation. This was in fact T'oegye's original arrangement. It has, however, the drawback of interrupting the close connection between this chapter and the two final chapters, which are devoted to the discussion of mindfulness, introduced here as the essence of self-cultivation.

But the "Treatise on Jen" is not only a discussion of jen; it is also a description of the mind that explains its fundamental character or substance as an integral continuation of the inner nature and dynamism of the whole universe. In this perspective, it is related to the structural considerations of the sixth chapter and serves as a fitting prelude to the discussion of the cultivation of the mind begun in this chapter. This is T'oegye's final arrangement.

The Ten Diagrams attempts to present a comprehensive vision of existence and elaborate its consequences for the way we form ourselves and carry on our daily life. In such a work, questions of a proper and coherent order of presentation have ramifications in which more is at stake than just logical coherence. What comes first has a direct bearing on the understanding of what follows. Thus changing the position of the "Treatise on Jen" makes it not just the final goal of all self-cultivation, but a basic commentary on the nature of the mind and the universe, a window through which to view the task of self-cultivation. This chapter approaches the concrete world of moral cultivation and cannot but show the mind with its forces divided between currents representing the original goodness of man's nature and the self-centered proclivities which attend our physical, individual existence. This side of Chu Hsi's thought was developed into what became, at times, an excessive rigorism tinged with a negative, suspicious attitude toward human feelings.41 Earnest moral concern and high seriousness were present in this, but one senses a loss of the grand, positive, overall vision which characterizes Chu Hsi's thought as a whole. The rearranging of these chapters places the discussion of moral self-cultivation and its natural emphasis on the need for constant

Diagram of the Study of the Mind 173

watchfulness and mindfulness in the clear overarching perspective of the "Treatise on Jen," and thus preserves the delicate balance of cautious optimism which is the Mencian heritage of the Ch'eng-Chu school.

NOTES

8. Diagram of the Study of the Mind

1. On the Classic of the Mind-and-Heart, see above, Introduction, "T'oegye's Learning. "

2. An early Ming dynasty scholar, Ch'eng Min-cheng (1445-1499+), produced the Hsin-ching fu-chu. His honorific name was Huang-tun. For a long time T'oegye had no information on his life, but finally became aware of an account which indicated certain flaws in his character, a revelation which was a heavy blow for T'oegye, as he recounts in his postscript to the Classic (Simgyŏng huron, TGCS, A, 41.12a-13a). Ch'eng's greatly expanded edition adds extensive quotes from Chu Hsi and Ch'eng I dealing with every aspect of mindfulness, making it rather prolix and repetitious. But T'oegye defended it when some of his pupils suggested that it should be reedited, saying that it already possessed a near classic status and was not to be tampered with (A, 23.30a-b, p. 562, Letter to Cho Sagyŏng).

3. On Ch'eng Fu-hsin, see above, chapter 2, note 32.

4. Hsin-ching fu-chu, table of contents, p. 5b.

5. A, 14.366, p. 378, Letter to Yi Sukhŏn.

6. On the development of the study of the mind-and-heart in the Yuan dynasty, see Wm. Theodore deBary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart, pp. 67-185; pp. 73-82 deal particularly with Chen's Classic of the Mind-and Heart.

7. This text appears in Hsin-ching fu-chu, table of contents, pp. 5a-b.

8. Mencius, 4B:12: "The Great Man is he who does not lose his mind of the infant."

9. Mencius, 6A:8. After describing how a mountain is deforested not because it is naturally barren but because of the constant violence cutting timber and pasturing animals have done its vegetation, he says: "As for man, how could he but have a mind of humanity and righteousness! The way he loses his naturally good mind is similar to the way the bills and axes [destroyed] the trees."

10. Book of Documents, pt. 2, 2.15. See below, Commentary, "The Human Mind and the Mind of the Tao."

11. See above, note 7.

12. Mencius, 6A:10.

13. See above, note 10.

14. Book of Documents, pt. 2, 2.15, and Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 20, respectively.

15. Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 1: "There is nothing more visible than what is hidden, nothing more manifest than what is subtle; therefore the superior man is watchful over himself when alone." As for the other items on this side, "overcome and return" is from Analects, 12:1: "To overcome oneself and return to propriety constitutes humanity." "The mind is present" refers to Great Learning, commentary section, ch. 7: "When the mind is not present, we look but do not see, listen but do not hear, eat, but do not know the taste. This is what is meant by saying that the cultivation of one's person consists of the rectification of one's mind." "Recovering the errant mind," comes from Mencius, 6A:11: "How lamentable it is to neglect the path and not pursue it, to lose one's [innately good] mind and not know to seek it! . . . The tao of learning is nothing other than seeking the errant mind, and that is all." "The mind is rectified" refers to the Great Learning, ch. 1: "Those who wished to cultivate their persons would first rectify their minds."

16. Mencius, 2A:2, in which Mencius says of himself, "At forty my mind was not moved [by high position, power, and the like]."

17. Mencius, 3B:2. This is from his description of "the great man."

18. Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 1: "The Tao cannot be separated from us for a moment; what can be separated from us is not the Tao. Therefore the superior man is cautious about what he does not see and apprehensive about what he does not hear." As for the other items on this side, "grasp and preserve" comes from Mencius, 6A:8: "Confucius said, "If you grasp it, it will be preserved; if you let it go, it will be lost. . . ' This is the characterization of the mind." "The mind exercises thought" refers to Mencius, 6A:15: "The office of the mind is thought. If it exercises thought, it attains [what is proper]; if it does not exercise thought, it does not attain it." "Nurturing the mind" refers to Mencius, 7B:35: "To nurture the mind, there is nothing as good as making the desires few." "Exhaustively realized" comes from Mencius, 7A:1: "He who has exhaustively realized his mind will know his nature; he who knows his nature knows Heaven. Preserving the mind and nurturing one's nature are the ways to serve Heaven."

19. Analects, 2:2, where Confucius says of himself, "At seventy, I could follow the inclinations of my heart and mind without transgressing what was right."

20. Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 20; this describes the qualities of a sage.

21. I-shu, 15.20a.

22. I-shu, 15.66.

23. A saying of Hsieh Liang-tso, HLTC, 46.146. These three sayings are among the most important early descriptions of mindfulness.

24. See Great Learning, ch. 1.

25. This was actually T'oegye's own major reservation about this diagram until he hit upon this solution. See A, 23, 276-296, pp. 561-562, Letter to Cho Sagyŏng.

26. Mencius, 6A:11.

27. Great Learning, commentary section, ch. 7.

28. Analecu, 6:7.

29. See Changes, Appended Remarks, pt. 2, ch. 4.

30. T'oegye especially praises Ch'eng Fu-hsin for his reluctance to serve a ruler whose proper claim to the throne was questionable (this was a Mongol dynasty), a quality highly emphasized by Korean Neo-Confucians (see Introduction on the "sarim mentality"), and also for his devotion to the pursuit of learning during long years of retirement, which T'oegye himself esteemed highly and sought with an urgency that approached almost desperation.

31. On these phrases, see above, notes 8-13.

32. Book of Documents, pt. 2, 2.15.

33. The "emptiness" of the mind refers to its being empty of any definite object, including the self (no innate self-centeredness) or any other object; hence it is universal in scope, able to respond to anything appropriately. T'oegye is thus inclined to attribute emptiness particularly to the "principle" aspect of mind in view of the transcendent all-inclusiveness and nonspecificity of principle. "Spirituality" (gong, ling) has to do with the mysterious, nonphysical mode of the mind's activity, which T'oegye attributes to the purity of subtlety (yong, ling) of he material force aspect of the mind's constitution. See Chŏnmyŏng tosŏl, ch. 6, B, 8.17a-b, p. 143. See also his lengthy defense of this position, especially with reference to relating principle and emptiness, which Ki Taesŭng critized: A, 16.40a-42a, pp. 421-422, Letter to Ki Myŏngŏn.

34. Hsin-ching fu-chu, l.la-b.

35. Wm. Theodore deBary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart, pp. 81-82.

36. A, 23.236-24a, p. 559, Letter to Cho Sagyŏng.

37. A, 25.19a-b, p. 600, Letter to Chŏng Chajung.

38. From the beginning of the Four-Seven Debate T'oegye saw the distinction between the Four Beginnings and Seven Feelings as paralleling the mind of the Tao and human mind, and one notes a similarity between his careful qualification of the human mind as initially `correct' and the recognition, forced upon him by Ki Taesŭng's criticism, that the Seven Feelings are originally "nothing but good." (See his comments in chapter 6 on the third diagram.)

39. deBary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart, pp. 81-82.

40. A, 14.40b, p. 380, Letter to Yi Sukhŏn.

41. On this development, see deBary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart, pp. 78-82. Ki Taesŭng's strong defense of the Seven Feelings in the Four-Seven Debate originated from his opposition to a current tendency in Korea that gave them no connection with man's original nature, a manifestation of a similar sort of excessive rigorism and negativity regarding the place of these feelings. See Sa chil i ki wangbok sŏ, 2.186, in Kobong chŏnjip, p. 281.