Chapter 5: DIAGRAM OF RULES OF THE WHITE DEER HOLLOW ACADEMY

| Contents | |

|---|---|

| Chu Hsi's Remarks on the Rules | 104 |

| T'oegye's Comments | 105 | Commentary |

| On the Essence of Learning | 107 |

| How to Read a Book | 108 |

| On Neo?Confucians and Worldly Confucians | 110 |

| Learning and the Political World | 112 |

| On Private Academies in Korea | 114 |

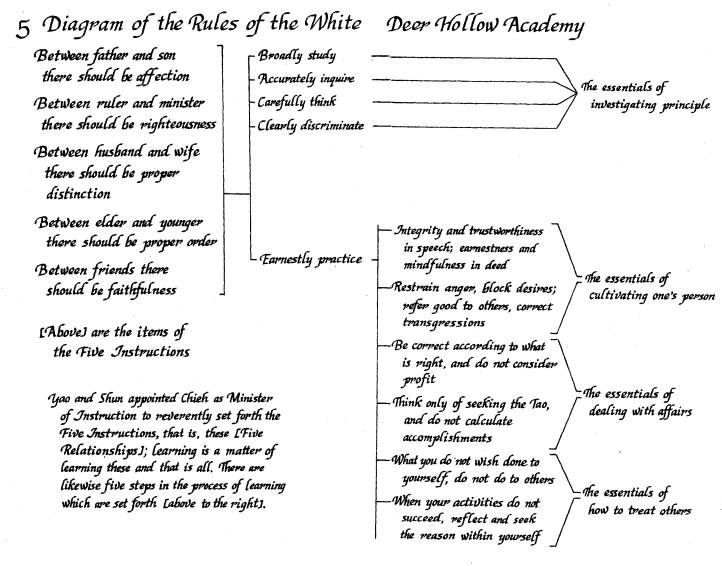

This is the last of the three chapters the Ten Diagrams devotes to the topic of learning. The chapters on Elementary Learning and Great Learning described the continuity of the learning process from youth to adulthood; they showed how from beginning to end it is a twofold process of study and practice and emphasized the role of mindfulness as its central methodology. The Five Relationships occupy a central place in the Elementary Learning, while the investigation of principle and the steps of practical self-cultivation and its expansion to include all of society are developed in the Great Learning. This chapter uses the rules Chu Hsi established for the White Deer Hollow Academy1 to show the structural integration of these themes: as presented here, the Five Relationships are not only the foundation, but the sum and substance of all learning, the object toward which all study and practice are ultimately devoted.

In his comments, T'oegye narrates the story of Chu Hsi's refounding of the White Deer Hollow Academy and mentions the official support it had earlier received from Emperor T'ai Tsung (960-976). T'oegye viewed such private academies (sŏwŏn, shu-yüan) as ideal institutions for Neo-Confucian learning, and was anxious to see them spread in Korea; for this, he felt, official royal sanction and support were essential. Hence there is a special point in his including this material in a document he hopes will be repeatedly perused by the king. The fifth section of the Commentary will discuss T'oegye's role in obtaining royal support for private academies in Korea and the important role they subsequently came to play in Yi dynasty society.

104 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

Chu Hsi's Remarks on the Rules 2

In considering the purport of how the ancient sages and wise men instructed others in the pursuit of learning, I find that it was totally a matter of explaining and clarifying moral principle for the cultivation of one's person; after [such cultivation was accomplished] it was extended so that [this rectifying influence] might reach others. It was never merely a matter of concentrating on memorizing readings and devoting oneself to literary composition in order to fish for a fine reputation and get a profitable salary. As for those who study nowadays, however, it is just the reverse.

Nevertheless, the methods whereby the sages and wise men instructed others are present in the Classics; students who have a firm intention [to pursue real learning] certainly should read and become versed in them, pondering deeply and inquiring into and discerning [their meaning]. If one understands according to principle what ought to be and takes it as his personal duty that it necessarily be so, then as for being furnished with rules and restrictions, what need will he have to wait for others to set them up in order to have something to follow and observe!

Nowadays there are rules for study, but they are only superficial in their treatment of those who pursue learning, and moreover the standards they present are not necessarily what the ancients had in mind. Therefore I will not restore any such rules to this hall; rather I have selected the great fundamental principles according to which all the sages and wise men have instructed others regarding learning, arranged them as above, and put them up on the eaves [of the hall].

May you gentlemen discuss and clarify [their meaning] among yourselves, practice and keep them, and take them as your personal responsibility; then the caution and fear with which you conduct yourself in your thought, speech, and activity

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 105

will certainly be more strict than these rules. But if at times this is not the case and one transgresses the bounds,3 then he must take up these so-called rules; they certainly cannot be neglected. May you gentlemen keep them in mind!

T'oegye's Comments

The above rules were made by Master Chu to be posted for the students of the White Deer Hollow Academy. The grotto was on the southern side of K'uang-lu Mountain in the northern part of Nan-k'ang Prefecture. During the Tang dynasty Li Po4 (fl. c. 810) while living there in retirement raised a white deer which followed him about, and the Hollow was named accordingly. During the Southern Tang (937-975) an academy was established there and named the National School (Kuo-hsiang); it always had several hundred students. Emperor T'ai Tsung (r.960-976) of the Sung dynasty showed his favor and encouraged the academy by bestowing books and giving an official rank to the head of the academy, but since then it had fallen into decay and ruin. When Master Chu was serving as Prefect of Nan-k'ang, he petitioned the court to restore it, assembled students, set up rules, and gave instruction in NeoConfucian learning (tao-hsiieh).5 Instruction in such academies subsequently flourished throughout the empire.

I have taken the items contained in the text of the rules and made this diagram of them so that one may easily see and reflect upon them. For the teachings of [the sages] Yao and Shun consisted in the Five Relationships, and the learning of the Three Dynasties was entirely a matter of manifesting proper human relationships. Therefore in the rules the investigation of principle and diligent practice are both based upon the Five Relationships. And although what is furnished in the rules and

106 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

restrictions of the learning of Emperors and rulers cannot be entirely the same as for ordinary students, insofar as they are based upon proper relationships and involve the investigation of principle and diligent practice as the essence of the method of properly cultivating one's mind-and-heart, there has never been any difference. Therefore I present this diagram with the others to furnish Your Majesty morning and night with "the admonitions of the Chamber Councilors.6

[T'oegye's note:]

The above five diagrams are based upon the Tao of Heaven, but their application consists in manifesting proper human relationships and devoting one's effort to the cultivation of virtue.

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 107

Commentary

On the Essence of Learning

The rules Chu Hsi wrote for study had great authority; in Korea they were written on the wall of the lecture hall of the Confucian Academy (Sŏnggyŭn'gwan), and T'oegye referred to them in directing his own students.7 When he wrote his own rules for the Isan sŏwŏn, he stipulated that the Rules for the White Deer Hollow Academy be written on its walls.8

In T'oegye's view the great value of these rules is that they express the essence of all learning, on whatever level, in terms of its fundamental content and basic methodology. When Pak Yŏng9 wrote a commentary on the Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy, T'oegye criticized it on a number of precise points of interpretation, but his most fundamental reservation was that Pak saw fit to introduce into his comments a discussion of "loftier" matters dealing with the substance of the Tao, the one thread running through all, and the like. T'oegye objected that these rules are perfect already, without going into such matters:

The learning of Master Chu is replete as regards both the integral substance and the great function.10 But in his setting up rules for those who pursue learning he particularly takes the Five Relationships as the foundation, which he extends in terms of the order of learning and finishes in terms of what is involved in earnest practice, without going as far as discussing the integral substance of the Tao as such; this likewise is the intent conveyed by the disciples of Confucius. In his way of teaching [as exemplified in these rules], the items which follow "broadly study" have to do with the extension of knowledge to the utmost, and those that follow "earnestly practice" have to do with diligent practice. He treats all the scholars of the world in terms of these two. Principle has no distinction between subtle and coarse; one begins from the coarser [understanding] and attains the subtler. Words encompass both loftier and lower levels; one studies the lower to arrive at the loftier. It is as when a flock drinks from a river and each is filled according to his

108 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

capacity. There are the lofty who are sages and wise men, and the more lowly who are good scholars; all can succeed with this approach. (A, 19,25ab, p. 479, Letter to Hwang Chunggo)

Particular topics are more suited to different levels of development, but even the loftiest or most profound of these, in the Confucian context, has its true significance in its bearing on one's proper conduct in relations with other human beings (i.e., the Five Relationships). Thus these rules transcend any topical discussion and are meaningful at all stages of learning and cultivation.

The five items of Chu Hsi's rules, from "broadly study" to "earnestly practice" are taken from the twentieth chapter of the Doctrine of the Mean. Of the four pertaining to the investigation of principle T'oegye focuses especially on the third "careful thought":

These four are the items involved in carrying knowledge to the utmost, and among the four, careful thought is by far the most weighty. What is the meaning of "thought"? It is seeking the matter out in one's own mind-andheart and having a personal experience and grasp of it. (A, 6.43b, p. 185)

This reminds us once again that learning in this context is a spiritual project, and the essential exercise of the mind is not speculative knowledge but personal transformation through a profound personal understanding and appropriation of what is studied.

How to Read a Book

True learning is not book learning, but books are nonetheless an important resource, for it is by the written word that the truths discovered by sages and wise men are crystallized and made available for personal reappropriation by later generations. We have already seen the aspect of reading which makes it a process of spiritual transformation, but the matter has further complexities: the synthesis of the Ch'eng-Chu school is woven of many strands and based upon a classical corpus which, even in its more limited Neo-Confucian

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 109

form,11 does not speak with a single voice. Personal appropriation of this material beyond the most elementary level becomes, for the NeoConfucian, a matter of achieving a level of insight in which discordant notes fall into place and the whole may be grasped as a polyphonic unity. This, needless to say, demands a fairly sophisticated hermeneutical process. T'oegye presents his approach as follows:

My own awkward method of reading books is this: whenever the sages and wise men speak of moral principle, when it is plain, then I follow its plainness and seek [the meaning] on that level and do not venture lightly to tie it to some hidden meaning; when it is hidden, then I follow its hiddenness and investigate it, not venturing lightly to associate it with what is plain. When it is on a shallow level, I base myself on the shallow and do not venture to bore through it and make it deep; when it is deep, then I approach it as deep and do not venture to stop at the shallow. Aspects they explain with analytical distinctions I look at as analytically distinct and do not take it as any harm to the fact of the undivided whole; what they explain in terms of an undivided whole I look at as an undivided whole and do not take it as any harm to there being analytic distinctions. I do not base myself on my private opinion and drag the left side and pull on the right in order either to join what has been analytically distinguished into an undivided whole or to separate the undivided whole to make analytic distinctions. Doing this for a long, long time, one naturally and gradually comes to see that there is a logic [underlying their sayings] with no room for disorder; one gradually perceives that the words of the sages and wise men, whatever manner of explanation they use, are each appropriate in their place and do not obstruct one another. (A, 16.42a-b, p. 422, Letter to Ki Myŏngŏn)

The fundamental assumption of an inner logic underlying diverse expressions is a hermeneutical equivalent of "principle is one but its manifestations are diverse"; it finds expression in T'oegye's confidence in the usefulness and feasibility of diagrammatic summaries (a form widely used in Korea) which are constructed on just this premise and are to be used as materials for prolonged reflective consideration along the lines suggested in this passage. His evident concern with the tension between distinctions and unity reflects the extent to which questions having to do with the dualistic monism of the philosophy of principle and material force, and the ramifications of both the distinctness and the interdependence of the two occupy his mind. 12

110 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

The other categories of interpretation, "the plain and the hidden," "the shallow and the deep," provide for the flexibility necessary for working through authoritative passages which at times seem to contradict one another. T'oegye is sharply critical when he feels students are just pulling out verbal contradictions from readings and making questions out of them, rather than quietly thinking them through to attain real understanding. On the other hand, such tools are counterproductive if their use is not controlled by a determined intent to really understand what a given passage is getting at. The unity of principle easily leads people in the direction of superficial syntheses which miss the true fruit to be gained by a more ripened working through of the materials and their problems:

In general, there is just a single principle which runs throughout the whole world and all creatures. Therefore if one does a rough and ignorant job of combining moral principle and verbal expressions into a thesis, there is nothing which cannot be made the same, and if one drags in [passages out of context] as pointing toward one's explanation, there is nothing which is not plausible. But in the end this does not [take into account] how at the beginning this was not the original intent of the words established by the sages and wise men. It is not enough for the discovery of the real teachings of the Classics, but finally suffices only to obscure the true principle and confuse one's actual insight [into it]. This is a pervasive problem among those who study. (A, 19.31a, p. 482, Letter to Hwang Chunggo)

One can see in these passages how "careful thought" is central as a means of both personal appropriation and scholarly rigor in study; the two are combined, for it is the objective truth profoundly grasped which is the instrument of personal transformation.

On Neo-Confucians and Worldly Confucians

When we look back at a certain period of Chinese or Korean or Japanese history and label it and the people acting in it as "Neo-Confucian," we generally do so because of the dominance of a

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 111

certain type of vision in the intellectual and spiritual world of the time which is typically reflected in the types of institutional arrangements and the kind of legitimizing rhetoric used by the society. Those who accept the intellectual framework, participate in the institutions, and use the rhetoric are ipso facto "Neo-Confucians."

The use of such generic labels is not illegitimate, but it may easily lead us to misunderstand the mentality of actual Neo-Confucians and the dynamics of their critical interaction with their society. The fact is, serious Neo-Confucians usually felt they were a minority set apart from the generality of men and the mores of the society surrounding them. Thus Chu Hsi in his remarks on his rules refers to the predominance of those who are engrossed in the pursuit of ends such as wealth and reputation, as opposed to the few who seriously pursue the kinds of ends inherent in true learning. T'oegye illustrates the same mentality in a set of exam questions on study which he gave when presiding over the civil service examinations. The following is indicative of the tenor of his set of questions:

Ah! Ah! Our land has been considered as having the heritage of Kija's instruction,13a country well-versed in ritual and propriety; and in addition we have a line of rulers who have one after another honored Confucians. But while the excellence of our valuing the Tao has reached such an extent, we still do not understand what it is to explain and make clear the learning of the true Tao [tohak, i.e., Neo-Confucianism].14 Not only do we not understand it; we shun it. Not only do we shun it, we become angry with it. Our looking at the writings of the sages and wise men does not go beyond regarding them as material for passing the civil service examinations and getting a salary. This is having a King Wen15 on the throne above, but no one rising [in response to his wisdom] below; this can only be a great shame for scholar-officials! (A, 41.41b, p. 931)

Neo-Confucian learning is in no way "otherworldly," but it demands the subordination of the ordinary worldly values which the majority make the framework of their lives. Although T'oegye was surrounded by fellow officials for whom the study of basic Neo-Confucian texts was a career prerequisite, he did not delude himself that many could trul~ understand the kind of learning project upon which his mind was set:

112 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

Worldlings all alike race along the path of honor and profit. If they succeed, they regard it as happiness; if they fail, they feel it a matter for anxiety and lamenting. The multitude are all like this. They do not understand what the wise find in the mountains and forests that they can plant themselves there and are able to forget about such values. But there is certainly something there! There is certainly something they attain! There is certainly something which they preserve and find peace in! There is certainly something which brings happiness to their hearts, but which others cannot understand as they do. I have my intent fixed on this, but have been as one wandering and lost with nowhere to go; how could I not strain toward it and thirst for it, and instead think about a few humiliating remarks that might be made?16 (A, 10.3a-b, p. 283, Letter to Cho Kŏnjung)

Learning and the Political World

T'oegye had long experience in a political world which often had proved treacherous and even deadly to idealistic, reformminded Neo-Confucians; he was one of the few who emerged relatively unscathed. He subscribed to the common Neo-Confucian view that learning and self-cultivation can perfect the ruler (or anyone else, for that matter) and thus lead to the transformation of society. But he was very realistic in assessing what normally happens. He tells King Sŏnjo:

Ah! Ah! If one does not begin there will certainly be no end; and if there is no end, what use will the beginning be? And in the learning of rulers, for the most part there is a beginning but no end. In the beginning they are diligent, and in the end, lax; in the beginning they are mindful, and in the end, licentious. (A, 7.46a, p. 186)

In his last interview with Sŏnjo, T'oegye analyzed the forces that play upon the king in bringing about the disastrous purges of upright scholar-officials as follows:

While King Myŏngjong (r.1545-1567) was still young the powerful and wicked had their way; when one would fall another would arise, so they

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 113

continued one after another to control things, and the disasters that befell the literati were more than one can bear to speak of.17 My informing Your Majesty of these past affairs is meant to serve as a great warning for the future. From ancient times rulers at the beginning of their governing have sought out the wise and talented, accepted remonstrance, and advanced the upright who would correct their transgressions and tell them their wrongs and draw their ruler back to the right path. Therefore in everything the ruler wanted to do, according to the matter in question they would contend with him and hold fast [to their position]18 The ruler, not getting to act freely, would become very leery of them and come to feel fed up and vexed. At this point the wicked would take the opportunity to win him over. The ruler, having in mind that if he were to employ these men he would be able to do whatever he wished, would for this reason consequently join with the inferior men and the upright and superior men would be left without a handhold. (OHN, 3.28b-29a, B, pp. 832-833)

T'oegye did all in his power to arm the young ruler against this, delivering strong lectures on the theme of relying upon the advice of upright ministers19 and warning against the desire to follow his personal inclinations as the root of all evil.20

He does not content himself, however, with simply laying the blame for these disasters upon worldly opportunists who thus ingratiate themselves with faltering rulers, grasp political power, and purge their more principled opponents. The pitfalls of the political world are not totally unforeseeable, and true, mature learning includes the wisdom to cope with the real world. T'oegye's deepest probing of the literati disasters is rather a critique aimed at the idealistic victims:

I have thought it strange that in the case of scholars in our country, if they are somewhat committed to learning and devoted to morality, for the most part they meet with disaster. Although this is [in part] because our land is small and its people illiberal, it is also due to something not yet complete in their own actions. That which I refer to as "not yet complete" is nothing other than the fact that their learning is yet imperfect while they occupy too high a position. They do not take the measure of the times but are courageous in attempting to set the world aright; this is the path by which they come to ruin. (A, 16.4b-5a, pp. 403-404)

The outstanding example of this-though there were many otherswas the meteoric career of Cho Kwangjo (1482-1519),21 in whose rise

114 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

to the pinnacle of power a generation of young idealists saw the sign of an approaching golden age, only to experience yet another purge of their ranks at his fall and execution at the age of thirty-seven. T'oegye admired him greatly and deeply lamented his loss, the more so, perhaps, because it might have been otherwise:

[T'oegye] once said: Cho Chŏngam's (i.e., Kwangjo) inborn talents were truly excellent, but the strength of his learning was not yet complete. His conduct of affairs did not escape having aspects that exceeded what was fitting, and therefore in the end he came to ruin his endeavor. If the strength of his learning had already been complete and the vessel of his virtue fully formed, and only then had he emerged and taken on the conduct of the world's affairs, what he might have accomplished would not be easy to measure. (OHN 5.5b-6a, B, p. 852)

What he has in mind by "learning" in such passages has nothing to do with subtle theories, but rather refers back to what we have seen in Chu Hsi's rules, which in the end make profound wisdom in the conduct of human relationships the final content of true learning. The rock upon which well-intentioned, personally upright and idealistic Korean Neo-Confucians too often foundered was pushing too hard too fast and too stubbornly, alienating others needlessly and bringing on head-on

clashes with established powers.

On Private Academies in Korea

Chu Hsi's Rules for the White Deer Hollow Academy conveniently focus and summarize the essential substance and elements of learning. But if that was all T'oegye wished to accomplish, it could have been done easily in the context of the discussion of the Elementary Learning and the Great Learning. It seems likely that an additional factor influenced his decision to include these rules in the Ten Diagrams: they were associated with Chu Hsi's reestablishing the White Deer Hollow Academy. Throughout the Ten Diagrams T'oegye is concise rather than expansive, yet here he dwells on the narrative

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 115

of the founding of the academy in a relatively leisurely and detailed fashion. In his mind this is more than merely a matter of the historical circumstances surrounding the rules: it is a paradigmatic action.22

T'oegye was, in fact, much concerned that the institution of such private academies should spread in Korea. He noted that there were over 300 such academies in Ming China, but that Korea had not yet emulated China in this regard. The first such academy was founded in Korea by Chu Sebong23 (1495-1554) in 1542 (completed in 1543), when he was magistrate of P'unggi County in Kyŏngsang Province. It was founded in honor of An Hyang,24 who had lived there and had first introduced Neo-Confucianism to Korea.

When T'oegye became magistrate of P'unggi in 1548, he devoted considerable attention to the White Cloud Hollow Academy (Paegŭndong sŏwŏn) founded by Chu. In 1549, shortly before he resigned, he wrote a long letter to the governor of the province in which he detailed the history of private academies in China, explained their importance, and, finally and most importantly, asked the governor to obtain direct royal approval and support, which would put the academy on a firmer footing and encourage others to imitate it:

In my humble opinion instruction must proceed from above and reach down to the lower levels; only then will it have roots which will enable it to last and endure for a long time. Otherwise it will be like water without a spring, full in the morning and gone by evening; how could it last long! Where the higher leads the lower will certainly follow; what the king honors the whole country will become devoted to . . . If this matter is not managed with a royal decree and its name not registered in the national records, then I fear there will be no way to stop public opinion on all sides and settle people's doubts and reservations about it25 so that [this academy] may become an effective model for the whole country and be perpetuated. (A, 9.6b, p. 263, Letter to Sim Pangbaek)

More concretely, T'oegye suggested that the king should emulate the example of Emperor T'ai-tsung of the Sung dynasty and express his support by granting a name-plaque in his own calligraphy, bestowing books, and even endowing it with fields and slaves. His suggestion was successful, and a plaque and books were bestowed by King Myŏngjong in 1550.

116 Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

After this the growth of private academies was rapid. During the reign of King Myŏngjong (1545-1567) at least sixteen were founded, and Myŏngjong followed his earlier precedent and awarded books and plaques to three more. King Sŏnjo's reign (1567-1608) saw an addition of 78, of which 20 were granted the royal favors. The development peaked in the reign of King Sukjong (r.1674-1720), during which 295 academies were founded and 132 given books and plaques by the throne.26 This brought the total number of private academies in Korea to more than 800,27 more than doubling the number T'oegye noted in Ming dynasty China.

Serious Neo-Confucian learning focused on mindfulness as central, and while this self-possessed, recollected state of mind encompassed both active and tranquil periods, it could best be cultivated initially in a relatively quiet and secluded environment, which came to be looked upon as the ideal circumstance, if not the absolute prerequisite, for serious application to learning. T'oegye championed the private academies because he saw them as the ideal institutional counterpart of the Neo-Confucian theory of self-cultivation:

What could they get from the private academies? Why were they so honored by China? Scholars who dwell in retirement in order to pursue their resolve, the group of those who investigate the Tao and verse themselves in learning, frequently become fed up with the world's noisy wrangling and pack up their books and escape to the broad and relaxed countryside or the quiet solitude of the seashore, where they can sing and recite[verses on] the Tao of the former sage kings, or be quiet and look into the moral principle of the world in order to nurture their virtue and ripen their humanity, regarding this as their pleasure. Therefore they are pleased to go to a private academy. They see that the national academies and district schools are located within the walls of the capital or local towns; on the one hand these[schools] are encumbered with the restrictions and obstacles of school regulations, and on the other they present temptations to turn toward other things. How could their effectiveness be compared with [the private academies]! Considered in this light, it is not only scholars' pursuit of learning which is strengthened by private academies; the nation's attainment of wise and talented men [to serve in government] will certainly by this means far surpass what could be accomplished through those [national and district schools]. (A, 9.5b, p. 263, Letter to Sim Pangbaek)

Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy 117

The rapid spread of private academies in the ensuing century witnesses the prestige of Neo-Confucian learning and the strength of its ethos among the yangban, the elite class which sponsored such institutions; but the mere fact that there were hundreds and hundreds of private academies does not necessarily indicate that the profound devotion to learning which T'oegye associated with them had become common and widespread. Learning was the chief legitimation of these institutions, but from the beginning of the seventeenth century and perhaps earlier, they came to have multiple functions, and learning was not necessarily foremost among these. In the generation after T'oegye's, factionalism became endemic in the Korean political world, giving rise to lasting cleavages along lines of regional, lineage, political, and even intellectual differences and loyalties. The private academies served as local bases for these factions, giving them a source of cohesion and a base of local power which enabled them to survive disasters at the capital. They were both a symbol of prestige and a means by which powerful families could glorify their lineages by publishing the collected writings of their illustrious forebears28 or by making them the object of semipublic veneration in the twice yearly sacrificial rites to exemplary Confucians, an important part of academy life.29 As much as centers of learning they were social centers which cemented relationships and maintained the ties by which these same families perpetuated their power and authority in local communities.

As these institutions multiplied and were transformed and politicized, criticism grew apace. They were continually criticized for their factional coloring, for their being used to glorify particular lineages, for the sometimes questionable qualities of the men they honored with sacrifices, for being more devoted to partying than to learning, and even for enlisting in their sometimes extensive slave rosters commoners attempting to escape corvee labor and military duty30 Attempts by the government to forbid establishing new academies began in 1655; these attempts became truly effective during the reign of King Yŏngjo (17241776), after which growth virtually stopped. During his reign some 300 were destroyed," but hundreds yet remained. Finally in 1871 it was decreed that all be destroyed except for 47, most of which remain to this day.

5. Diagram of Rules of the White Deer Hollow Academy

NOTES

1. The rules appear in CTTC, 74.16b-17a; T'oegye has left out one sentence which distributes the items which belong to the investigation of principle and earnestly practicing, for this distribution is graphically evident in his diagram.

2. These remarks immediately follow the rules, ibid., 74.17a-b

3. The CTTC text employs a different phrase here, but the meaning is essentially the same.

4. A scholar, not to be confused with the famous Tang poet, Li Po.

5. Tao-hsüeh (Kor. tohak), literally "the learning of the (true) Tao" is a common designation for the Ch'eng-Chu school of thought. It focuses particularly upon the serious moral concern which was central to this movement, but it also implies a fullness of truth, and its appropriation by this school of thought aroused considerable antagonism during Chu Hsi's lifetime.

6. See above, Address on Presenting the Ten Diagrams, p. 00.

7. See, for example, Letter to Kim Ijŏng, TGCS, A, 29.1Ob, p. 681.

8. Isan wŏngyu (Rules for the I Mountain Academy), TGCS, 41.52a, A, p. 936.

9. The courtesy name of Pak Yŏng (1471-1540) was Chasil, and his honorific name Songdang. He was primarily a military man and came from a military family, but spent the years 1494-1506 (the reign of Yŏnsan'gŭn) in retirement chiefly studying the Great Learning. His collected works are entitled Songdang chip.

10. "Integral substance" is the perfect fullness and wholeness of principle; "great function" is the correlated active and perfect responsiveness to all creatures and circumstances. These stand for the ultimate perfection; thus Chu Hsi describes the final perfection of the investigation of principle and the extension of knowledge in these terms in the passage he introduces to supplement for the "lost" fifth chapter of the commentary section of the Great Learning.

11. Chu Hsi was largely responsible for the emergence of the Four Books (Great Learning, Analects, Mencius, and Doctrine of the Mean) as the authoritative core of the classical corpus; he held that these works contained the words of Confucius and Mencius, while the other Classics were to varying degrees further removed and less reliable reflections of the masters' teachings. On Chu Hsi's revision of the classical corpus and its significance, see Wing-tsit Chan, "Chu Hsi's Completion of Neo-Confucianisml," pp. 81-87.

12. See below, chapter 6, on the Four-Seven Debate, which was centered on these issues as they relate to understanding the relationship of human nature and kinds of feelings. This passage is part of one of the important letters of the debate.

13. On Kija, see Presentation, note 16.

14. On tohak, see above, note. 5

15. The sage King Wen (1184?-1135? B.C.) was the founder of the Chou dynasty.

16. This letter, written in 1543, is the earliest indication that T'oegye had resolved to resign and withdraw from public life. The "humiliating remarks" he mentions refers to the fact that in the atmosphere which prevailed any such attempt would be (and was) cynically criticized as a self-serving evasion of public duty.

17. Cf. Introduction, "Rise of the Sarim Mentality and the Literati Purges."

18. The early years of the reign of Yonsan'gun (r. 1494-1506) are a clear example of this, for he was blocked at every turn by stubborn resistance and criticism from the three powerful official organs of remonstrance, the Office of the Inspector

General, the Office of the Censor General, and the Office of Special Councilors. There ensued the bloodiest and most violent purges of Neo-Confucian officials in Yi dynasty history. See Edward Wagner, The Literati Purges, pp. 33-69.

19. See especially his Kan Kwae sanggu kangŭi (Lecture on the Uppermost Yang Line of the Ch'ien Hexagram), TGCS, A, 7.48a-49a, pp. 217-218. This was a theme to which he frequently returned in his talks with King Sŏnjo.

20. See his Mujin kyŏngyŏn kyech'a i (Second Exposition of 1568 from the Classics Mat), TGCS, A, 7.3a-4b, p. 195, which is devoted entirely to this theme.

21. See Introduction, "Rise of the Sarim Mentality and the Literati Purges." T'oegye wrote his biography, which appears in TGCS, A, 48.28a-38a, pp. 1061-1066.

22. T'oegye uses it in this way in the letter in which he appeals for official royal sanction of the White Cloud Hollow Academy. See Letter to Sim Pangbaek, TGCS, A, 9.4a-8b, pp. 262-264.

23. The courtesy name of Chu Sebong was Kyŏngyu, and his honorific name Sinjae. His subsequent career included posts as Headmaster of the Confucian Academy and Governor of Hwanghae Province, where he established another private academy which in 1555 was honored with a royal bequest of a name plaque and books.

24. On An Hyang, see Introduction, "The Late Koryŏ-Early YI Transition period. "

25. Earlier in this letter T'oegye mentions that in founding this academy Chu Sebong had to overcome criticism from those who questioned his action and thought it strange.

26. These figures are taken from a table in Yi Ch'unhŭi, Yijo sŏwŏn munch'ang ko (Investigation of the Library Collections of Yi Dynasty Private Academies), p. 17.

27. Ibid., p. 16. The table on p. 17 lists a total of only 650 private academies; there is no indication of where the figure of "over 800" comes from; perhaps it takes into account the fact that the records upon which the table is based are not exhaustive.

28. After the Japanese Invasions (1590-1598) publishing became a common function of the private academies. Their libraries were an important local cultural resource. The core of these libraries was the standard Neo-Confucian collection of the basic works of the Ch'eng-Chu school such as the Chu Tzu ta-ch'üan, Chu Tzu Yü-lei, Hsing-li ta-ch'üan, etc. Included also were Korean works, but generally an academy would include only works associated with the intellectual lineage of its own faction, so the minds of those educated in this context were already biased regarding the major issues debated in the course of the Yi dynasty. About 80 percent of the publishing activities were devoted to munjips (collected writings) and memoirs selected according to factional ties. See ibid., pp. 22-25.

29. These rituals had a formative or educational function insofar as they were occasions for reflecting upon and honoring ideal role models. But even in the earliest (1595) memorials questioning the development of these academies, it is mentioned that many who are so honored in various academies are in fact insignificant personages. Ibid., p. 18.

30. Ibid., pp. 16-18.

31. Ibid., p. 21. Page 19 presents a chart describing 25 restrictive measures the government took against the academies between 1655-1871; 19 of these measures fall in the first 100 years of that period, reflecting their general ineffectiveness until 1741, when harsh sanctions were enacted and 300 academies actually were destroyed.