From Pagan to Christian:

The Story in the 13th-Century Tapestry of the Skog Church,

Hälsingland, Sweden

by Terje Leiren

University of Washington, Seattle

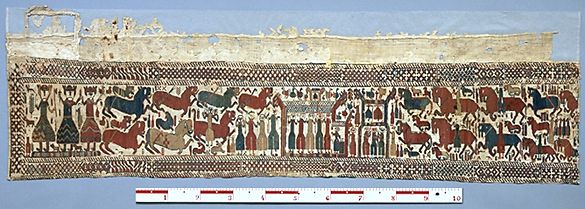

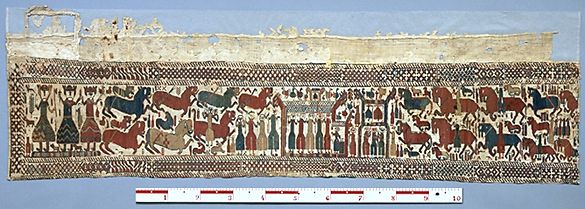

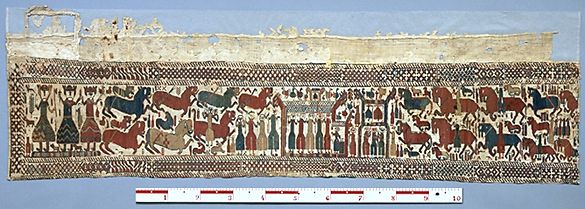

The Skog Church Tapestry

This woolen tapestry on a white linen background is believed to date from the

late 13th Century, after Sweden's conversion to Christianity.

The tapestry, originally from the Skog Church in Hälsingland, Sweden,

has been in Stockholm's Museum of National Antiquities (Statens Historiska Museum)

since 1914. It is more than just a tapestry, it tells a story of a culture in

transition.

The tapestry contains a stave church in the center with a congregation

inside the church. On the eaves of the church roof are two dragon heads.

There is a bell tower in the church and another next to the church itself.

Animals, believed to be lions, are approaching the church from the left,

while horses, and soldiers/knights, approach from the right.

Traditionally, this has been seen as the church under attack. To the far

left of the tapestry are three figures, usually thought to be Scandinavian

kings/saints Olaf, Knud, and Erik. In fact, these are not only Christian

saints.

The Viking Trinity

According to Adam of Bremen: "If plague and famine threatens, a libation

is poured

to the idol Thor; if war, to Odin; if marriages are to be celebrated, to

Frey."

Because Odin, the All-Father, was generally more feared than loved and

subsequently kept at a distance, his son, Thor, assumed the position as

favored

deity. He was the protector and trusted friend. Some myths associated

with

Thor had him as almost human, with his foibles and gullibility. His

hammer came

to be used as an amulet, not only to signify the wearers allegiance to the

old

faith, but also as protection against the evils abounding. Odin

and

Thor were the most prominent members of the militaristic Æsir

family. Frey, god of fertility and fecundity, led the Vanir family, the

early

opponents of the Æsir. However, a truce between them brought Frey to

Valhalla and elevated his status to be one of the Norse trinity.

With the

conversion to Christianity, the Norse trinity, although driven

underground by the Christian church, nevertheless, remained significantly

conspicuous, albeit in changed form. Scandinavian/Viking kings could

easily be depicted as representions of the earlier pagan deities without

the authorities of

the Roman Church being any the wiser. In the same way that an anonymous

woodcarver craftsman working on the Borgund Stave Church in western

Norway could put a representation of the one-eyed Odin on the top of a

column in the dark upper reaches of the sanctuary, so too could an

artisan represent the pagan gods as medieval kings and/or saints.

Consequently, with his axe, St. Olaf came to be associated with Thor and

his hammer. In the tapestry, however, there seems to be a mixing of

deities, as St. Olaf with his axe represents not Thor, but the one-eyed

Odin who is placed next to a representation of a tree, perhaps the

Yggdrasil from which he had hung. In addition, King Knud, killed at the

alter of St. Albans Priory in Odense, Denmark, is placed in the middle,

holding a Thor-like hammer(the crucifix?), while King Erik ( the fertility

diety, Frey) flanks him on his right holding an ear of corn. This

arrangement, with Thor in the middle, is similar to Adam of Bremen's

description of the idols in the great temple at Uppsala where Thor is said

to be flanked by Odin and Frey.

The Bells

It was generally believed by medieval Scandinavians that bells cleansed the air,

purging it of evil spirits. According to Rimbert in his Life of St.

Ansgar, church bells were considered unlawful by pagans. Perhaps they

frightened the spirits. Christians, of course, had no such qualms, indeed they

probably sought to intimidate those very same spirits protected and

nurtered by the pagans. Bells, of course, called the Christian faithful to

worship, but there was a far stronger symbolism at work. When Gustav

Vasa, during the Lutheran Reformation, around 1527, began confiscating

church bells for metal to help restore the state treasury, it aroused such

indignation among the citizenry that his royal authority itself was

threatened and pretenders to the throne began calling for his

overthrow.

Dragons and Other Animals

Just as bells frightened spirits and cleansed the air around a Christian

church, dragon heads were placed on the roofs of stave churches to

frighten away evil spirits. Although today, animal heads on the stave

churches give it a quaint appearance, their use in the architectural

structure in the 12th and 13th

centuries was, however, very serious business. In old Icelandic law, it

was

illegal to bring a ship, with its dragon-head bow, directly into land for fear of

offending the spirits of the land. Christian converts did not give up their

traditional beliefs in pagan spirits, but instead of protecting and placating

the spirits, it was the church and the worshippers inside which now had to

be

protected. Dragon heads, therefore, served a useful purpose as a part of

the church structure. Dragon heads on the church in the Skog Tapestry

face out as a protective force for the Christian faith, the faithful and

the physical structure of the church itself.

The dragon is only one of a number of animals (real and mythical) in the

Viking religious universe. While the dragon is attacking the roots of the

Yggdrasil (the World Tree), a squirrel runs up and down carrying insults

between the dragon and the eagle in the canopy of the tree. Most

prominently, of course, the Fenris Wolf and the World Snake are two of the

representations of evil and chaos itself in the Norse world view. All

animals were not evil or threatening. In Christian Scandinavia, the lion,

an animal not found in Scandinavia, represents power and royal prestige.

In the pagan world, Odin is also associated with animals --his

magical horse, Sleipnir, and his two ravens (Hugin and Munin) who served as his

"eyes and ears to the world," bringing him news of all developments.

Conclusions

The transition from Paganism to Christianity in Scandinavia was not an

easy one

for Scandinavians to make. The Swedish writer, Vilhelm Moberg, called it the

"300-year War." From the time of the appearance of the first Christian

missionaries in the early 9th century until the final conversions in the

11th and 12 centuries, Pagan Scandinavia was under constant pressure from

the forces of the "White Christ."

When leaders converted, pressure on the people was increased, of course.

Olaf Trygvasson's forced conversions in Norway, as well as Charlemagne's

two hundred years before him in Saxony, were no less brutal than any pagan

Viking raid. The transition between paganism and Christianity, however

brutal and uncertain it might have been, nevertheless, saw a merging of

cultures and beliefs. The art and the architecture of the time certainly

demonstrate this. We see it reflected in various elements of stave church

construction and also in such things as the Skog Tapestry.

What, then, of the numerous gods and spirits? Many survived by

going underground and are found in Scandinavian folklore and popular

belief.

Trolls are not unlike the giants of Jotunheimen who constantly battled the gods

allied against them. In some instances, trolls are just as dim-witted as

the giants themselves appear to have been. The principle deities,

however, were too easily recognized by the authorities in the Church, and

were, therefore, forced to take deeper cover. If you look carefully,

however, you can occasionally find them in medieval iconography, often

disguised as kings or saints. What better way to keep Thor and Odin alive

and out of the clutches of the Christian authorities than to dress them up

to look like medieval Christian saints?

Terje Leiren

Department of Scandinavian Studies

University of Washington

Copyright © 1999-2019, Department of Scandinavian Studies, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

98195-3420