Of the many possible ways to distribute earth, water and sky in a landscape painting, some in particular seem to have proved satisfying at a deep level, and to have become very widespread. The arrangement in the painting on the left was pervasive in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Earth is in the foreground, water the middleground and sky the background, but to give the composition interest, the principal foreground mass of land and vegetation is made to reach up one side of the painting, the lake or river of the middleground is deployed low on the other side, and the sky fills the remaining area, in this case the upper left quarter. This is a Dutch vision of the Holy Lands, Aelbert Cuyp's The Flight into Egypt (mid-1650s).

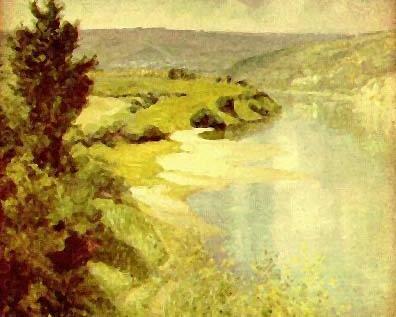

The landscape on the left, painted nearly two centuries later and a thousand miles away, has almost exactly the same disposition of earth, water and sky. It is a provincial Russian work, A. V. Tyranov's View of the Tosna River near Nikolskoe (1827). There is no question of direct influence here, although there is certainly some generalized influence of Dutch landscape art on Russian. It's just a striking example of the pervasiveness of a particular compositional cliché over the history of European landscape painting, and countless other examples can be found. However, even though the ravines and river banks of Russia can yield landscapes with steep containing slopes, the terrain that came to be regarded as quintessentially Russian is...

... the flat expanse viewed from just high enough for its extent to be appreciated. This kind of view implies a different distribution of earth and sky, and of water if it is present. It also of course implies a radically different composition. The painting on the left is Apollinarii Vasnetsov's Motherland (1886). Its title makes this painting worth looking at particularly closely as an essentially Russian scene. The emphasis here is on the inhabited landscape. Though the terrain is flat, there is only slightly less land than sky. The land has enough relief for the cottages in the middleground to nestle in a hollow, but is flat enough for there to be a distant church on the horizon. There is no large expanse of water to suggest the desolate aspect of nature, and there are reassuring signs of cultivation.

Russia isn't of course the only European country where painters have made poetry of the flat landscape. On the left is a Dutch example: Anthonie van Borssom's Extensive Landscape near Rhenen with the Huis ter Leede (1660s) combines road, river, castle and church with hints of ordinary dwellings, a figure in the foreground, and the cattle that are almost a trademark detail of domestic landscapes throughout Europe. In nineteenth-century Russia, the "extensive landscape" acquired trademarks of its own. It could contain most of the routine components of its European counterpart, but the proportion of sky to earth was generally higher, and more often than not, a river was prominent in it: Russia's geography is to a large extent defined by its vast rivers, and they naturally loom large in Russians' consciousness of their native land.

Polenov's The River Oka in the Summer has the river as its subject, framed by land that has a substantial amount of relief, and a tree in the foreground. The sky is in the minority in this painting. This is common enough in Russian landscapes that are centered on small bodies of water, but where the focus is major rivers, it is more usual for the sky to be the dominant component. The difference isn't trivial: it reflects a fundamental choice between two opposing perceptions of nature. On the one hand, there is the celebration of nature tamed, a landscape in which:

On the right is a Russian example of the desolate landscape, Arkhip Kuindzhi's Morning over the Dniepr (1901). The early morning haze blurs the distinction between the raised land of the foreground, the immense river winding through the middleground, and the distant land and background sky. The human element is all but excluded from the scene, and the most prominent feature is a thistle. This painting illustrates very well the resurgence of the Romantic landscape vision in Russia around the turn of this century, in the service of a "poetic realism" that had a distinctly nationalist flavor.

On the right is the lower part of Ivan Shishkin's Midday. Near Moscow, which is explored in detail in the section on The Russian Combination. In this painting elements of the extensive, desolate landscape (three-quarters of the painting is sky, as you can see by enlarging the image) are cleverly blended into a friendlier, more bucolic scene in which people figure prominently. The result combines the two poles of the European landscape vision in a way that is not just visually Russian, but can be shown to echo a characteristic trend in late-nineteenth-century Russian intellectual history.

Again, such paintings aren't confined to Russia: hybrid landscapes combining the human scale with something vaster can be found in the Dutch tradition, too. On the left is Jacob van Ruisdael's Wheatfields (late 17th century), in which a road with figures on it leads away through an expanse of cultivated land to a sky that strongly dominates the whole scene. In theme and composition it matches Shishkin's Midday very closely, but there are some interesting differences: