THE MONSTER BEHIND THE DOG

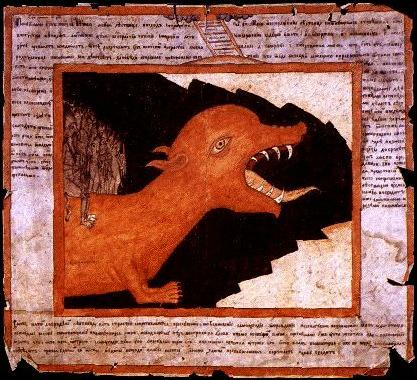

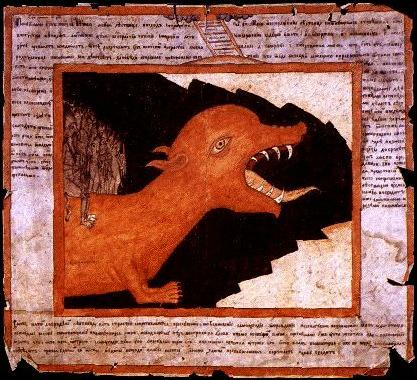

On the left is an anonymous painted lubok from around 1850, showing a monster at the mouth of hell, its back loaded with sinners.

On the left is an anonymous painted lubok from around 1850, showing a monster at the mouth of hell, its back loaded with sinners. In Byzantine and Russian iconography, the black background with a jagged outline is an almost ubiquitous convention for representing the mouth of hell, whether at the foot of the cross in icons of the crucifixion, or in other contexts. On the right for comparison is the triple head of Cerberus from a Greek vase of the late 6th century BC. The key details of the monster in the Russian image are the large rounded head with a pronounced forehead and small ears placed far back, the upturned snout, usually with wrinkles along its top, the long and often sharply back-curved teeth in a gaping mouth, the thick pointed tongue curving out from the mouth, and the three-toed feet. Notice that although the Cerberus on the Greek vase is a much more realistic portrayal of a dog, all the key features are present, and may have been progressively stylized and exaggerated in later repetitions of a commonplace Greek image. The open mouth as an attribute is reflected in Virgil's description of the entrance to Hell in the Georgics (36-29 BC): "Cerberus held his three mouths gaping wide..."

In Byzantine and Russian iconography, the black background with a jagged outline is an almost ubiquitous convention for representing the mouth of hell, whether at the foot of the cross in icons of the crucifixion, or in other contexts. On the right for comparison is the triple head of Cerberus from a Greek vase of the late 6th century BC. The key details of the monster in the Russian image are the large rounded head with a pronounced forehead and small ears placed far back, the upturned snout, usually with wrinkles along its top, the long and often sharply back-curved teeth in a gaping mouth, the thick pointed tongue curving out from the mouth, and the three-toed feet. Notice that although the Cerberus on the Greek vase is a much more realistic portrayal of a dog, all the key features are present, and may have been progressively stylized and exaggerated in later repetitions of a commonplace Greek image. The open mouth as an attribute is reflected in Virgil's description of the entrance to Hell in the Georgics (36-29 BC): "Cerberus held his three mouths gaping wide..."

An early 17th-century icon by Nikifor Savin, Fedor Tiron and the Dragon (left), fills the mouth of hell with a swarm of very different-looking monsters that still have the same basic features - long teeth, a long tongue, a forehead, ears at the back of the head, and feet with three clawed toes. Most of these features can be found on the beasts on the right, a detail from an eleventh-century Byzantine ivory-carving, the cover of Queen Melisende's Psalter. These fighting creatures have a more dog-like appearance, and the same stylized posture as young Nicholas Temerin's dog on the previous page - click on the psalter-cover on the right to compare the two. In the Greek tradition the guardians of the entrance to the underworld are explicitly dogs, and they are represented as such in some Byzantine paintings. However, the same stylized head appears on images of the "whale" that swallowed Jonah, and quite frequently on the great serpent slain by St. George.

Most of these features can be found on the beasts on the right, a detail from an eleventh-century Byzantine ivory-carving, the cover of Queen Melisende's Psalter. These fighting creatures have a more dog-like appearance, and the same stylized posture as young Nicholas Temerin's dog on the previous page - click on the psalter-cover on the right to compare the two. In the Greek tradition the guardians of the entrance to the underworld are explicitly dogs, and they are represented as such in some Byzantine paintings. However, the same stylized head appears on images of the "whale" that swallowed Jonah, and quite frequently on the great serpent slain by St. George.

In Byzantine iconography the distinction between "whale", serpent and dragon is blurred. The image on the left is from the Khludov Psalter, a ninth-century Byzantine manuscript that was brought to Russia from the Balkans in the 1840s. It illustrates the story of Jonah, who can be seen inside the belly of a beast with the head and forefeet of a dragon, the coiled body of a serpent, but the tail and the fins (on the side of the neck) of a fish.This is a widespread image in the ancient Mediterranean world: compare below...

... the embossed gold figure of a sea-nymph riding a monster, on the lid of a silver box of the late second century BC (on the right). The important details are essentially the same as Jonah's monster in the Khludov Psalter: the dog-like dragon's head with little ears and a row of curved teeth, the coiled body with a fish's tail and a fin at the side of the neck (just visible below the nymph's right arm), and the forelimbs, which here are more like fins, but divided into digits. The only significant difference is that the nymph rides atop the serpent, while Jonah travels inside it.

Even in late Byzantine times the head of this conventional monster, derived from the Greco-Roman tradition, could be explicitly canine. A good illustration is the image on the left, from a scene of the Last Judgment in a Byzantine illuminated gospel book of the mid-eleventh century. Serving in its context as the entrance to hell, this creature has the head and forelimbs of Cerberus himself (the artist has shown two heads, each swallowing one of the damned) and the coiled body of the serpent, ending in a fishtail. Mounted astride one of the heads is a figure of Hades, the Greek god of the underworld.

In a world in which visual culture has a central importance, pictorial images can be remarkably long-lived and stable. This phenomenon, and cultural influences over the course of centuries, explain how some of the characteristic details of a monster from the ancient Mediterranean world can surface on the head of a Russian lap-dog some two thousand years later.

Most of these features can be found on the beasts on the right, a detail from an eleventh-century Byzantine ivory-carving, the cover of Queen Melisende's Psalter. These fighting creatures have a more dog-like appearance, and the same stylized posture as young Nicholas Temerin's dog on the previous page - click on the psalter-cover on the right to compare the two. In the Greek tradition the guardians of the entrance to the underworld are explicitly dogs, and they are represented as such in some Byzantine paintings. However, the same stylized head appears on images of the "whale" that swallowed Jonah, and quite frequently on the great serpent slain by St. George.

Most of these features can be found on the beasts on the right, a detail from an eleventh-century Byzantine ivory-carving, the cover of Queen Melisende's Psalter. These fighting creatures have a more dog-like appearance, and the same stylized posture as young Nicholas Temerin's dog on the previous page - click on the psalter-cover on the right to compare the two. In the Greek tradition the guardians of the entrance to the underworld are explicitly dogs, and they are represented as such in some Byzantine paintings. However, the same stylized head appears on images of the "whale" that swallowed Jonah, and quite frequently on the great serpent slain by St. George. On the left is an anonymous painted lubok from around 1850, showing a monster at the mouth of hell, its back loaded with sinners.

On the left is an anonymous painted lubok from around 1850, showing a monster at the mouth of hell, its back loaded with sinners. In Byzantine and Russian iconography, the black background with a jagged outline is an almost ubiquitous convention for representing the mouth of hell, whether at the foot of the cross in icons of the crucifixion, or in other contexts. On the right for comparison is the triple head of Cerberus from a Greek vase of the late 6th century BC. The key details of the monster in the Russian image are the large rounded head with a pronounced forehead and small ears placed far back, the upturned snout, usually with wrinkles along its top, the long and often sharply back-curved teeth in a gaping mouth, the thick pointed tongue curving out from the mouth, and the three-toed feet. Notice that although the Cerberus on the Greek vase is a much more realistic portrayal of a dog, all the key features are present, and may have been progressively stylized and exaggerated in later repetitions of a commonplace Greek image. The open mouth as an attribute is reflected in Virgil's description of the entrance to Hell in the Georgics (36-29 BC): "Cerberus held his three mouths gaping wide..."

In Byzantine and Russian iconography, the black background with a jagged outline is an almost ubiquitous convention for representing the mouth of hell, whether at the foot of the cross in icons of the crucifixion, or in other contexts. On the right for comparison is the triple head of Cerberus from a Greek vase of the late 6th century BC. The key details of the monster in the Russian image are the large rounded head with a pronounced forehead and small ears placed far back, the upturned snout, usually with wrinkles along its top, the long and often sharply back-curved teeth in a gaping mouth, the thick pointed tongue curving out from the mouth, and the three-toed feet. Notice that although the Cerberus on the Greek vase is a much more realistic portrayal of a dog, all the key features are present, and may have been progressively stylized and exaggerated in later repetitions of a commonplace Greek image. The open mouth as an attribute is reflected in Virgil's description of the entrance to Hell in the Georgics (36-29 BC): "Cerberus held his three mouths gaping wide..."