|

“The Shaping of California History”

by James N. Gregory

This essay traces the geopolitical and demographic history of California. It appeared originally in the Encyclopedia of American Social History (New York: Scribners, 1993); an abreviated version was republished in Major Problems in California History , eds. Sucheng Chan and Spencer C. Olin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997) |

|

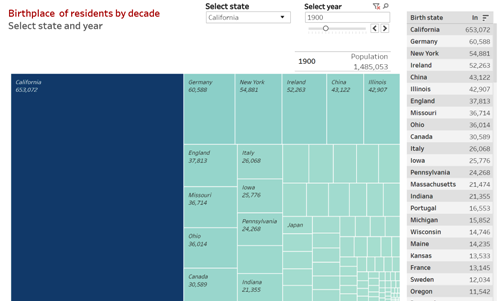

California Migration History 1850-2010

click below to explore the state's migration history with an interactive chart and decade-by-decade data

James N. Gregory has published two books and several articles on aspects of California history.

American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).Winner of the 1991 Ray Allen Billington Prize from the Organization of American Historians; winner of the 1990 Annual Book Award from the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association.

"Dust Bowl Legacies: The Okie Impact on California 1939-1989" California History (Fall 1989)

"The West and the Workers, 1870-1930" in A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 240-55

"The Dust Bowl Migration," in Poverty in the United States: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and Policy, eds. Gwendolyn Mink and Alice O'Connor (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2004)

Upton Sinclair. I, Candidate for Governor, and How I Got Licked. Introduction by James N. Gregory (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994) |

California is not just another state. Lord James

Bryce saw that over a century ago when he devoted a

chapter of his two-volume study of the American

Commonwealth to California "because it is in many

respects the most striking in the whole Union, and has

more than any other the character of a great country,

capable of standing alone in the world." In

the 1990s that statement no longer carries surprise.

With its citizenry now exceeding thirty million, there

are more Californians in the world than there are

Canadians, Australians, or Greeks; more Californians

than Czechoslovakians and Hungarians combined; more

than all the Scandinavians in Sweden, Norway, and

Denmark. Still larger is the state's share of global

economic activity. California's gross domestic product

makes it the eighth largest economy in the world;

larger than People's Republic of China, just behind

Great Britain and Italy. And if consumption is the

measure, the California presence looms still larger.

Californians possess more automobiles, VCRs, and

personal computers than all but the United States and

four other countries, each with at least twice its

population. The state enjoys the same distinction in

the consumption of water, petroleum, chemicals and in

the generation of trash.

But Bryce was not talking about size. In 1889 he

located the uniqueness of California in its exuberance,

its unconventionality, its admixture of populations,

and most of all in its location, half a continent

removed from the rest of American civilization. An

outpost on the Pacific, California was in Bryce's day a

staging ground for the resettlement of the final third

of the continent, the mountain and Pacific West--a

mission that encouraged its premature expressions of

grandeur and spirit of independence.

Nowadays the mission has changed. The state's

function within the national community is no longer

peripheral. In the regional restructuring of the late

twentieth century, California has emerged as the

nation's second financial and cultural center, a rival,

though still junior, to the East Coast power corridor.

Global economic shifts and the massive internal

redistribution of peoples, industries, and public

policy priorities since World War II have turned the

United States into a bi-polar nation. California is the

capital of the newer America that faces west and south

towards Asia and Latin America.

The state's growing authority in world and

national affairs rests least of all on formal politics.

Although Southern California money and celebrity play a

large role in national politics, and while three of the

last four Republican presidents have been Southern

Californians, it is in the realms of business and media

that California's influence is chiefly felt. The

state's relationship with Japan and the Pacific Rim is

key. California is the chief port of entry for Japanese

goods and capital and the Japanese for that reason

collaborate in the development of this west coast power

center. One of their contributions is to the already

powerful California banking industry. America's high

tech electronics and bio-science industries, heavily

concentrated in the state, also boost California's

international authority while further tying the state

to Japan and other Pacific Rim countries.

Media is the other leg on which California rises.

First with the advent of Hollywood as the international

film capital in the 1920s, then with the addition of

television studios in the 1950s, Southern California

has exerted an enormous role in the production of

popular entertainment and the consequent shaping of

consumer values. In the last two decades, Los Angeles

has also made a multi-billion dollar effort to become a

high-culture capital with the establishment of new

museums (the Getty, the Norton Simon, the Armand

Hammer, the Museum of Contemporary Art), symphonic and

performing arts centers, and dozens of theatre groups.

As Mike Davis notes in City of Quartz, his penetrating

study of Los Angeles in the 1980s, Southern

California's elites are currently engaging in the kind

of wholesale art grab that brought "culture" to gilded

age New York a century ago.

Like Texas and one or two other states, California

is really a region unto itself. Geography makes it part

of the western United States but history sets it

partially outside the regional culture area called the

West. To be sure it shares with the other states of the

Pacific and Mountain time zones a number of

characteristics that lend coherence to the region. It's

topography--mountains, valleys, deserts--is decidedly

western as is its mostly arid climate and resulting

water distribution problems. Its political-economy also

followed regional patterns: cities, mining, and

railroads came first, then agriculture; the federal

government owned and still owns much of the land and

played and still plays a critical role in economic

development. Furthermore one can speak of the state's

politics as western. Turn-of-the-century sectional and

developmental conflict yielded a western "progressive" political system, with weak parties, strong executives,

and liberal provisions for voter initiative. Also in

the western mode, California has remained throughout

the twentieth century a stronghold of Republicanism.

But there are other historical features that it

does not share with other western states, matters of

demography and mythology that advance California's

claim to uniqueness. Underpopulation and a system of

ethnic relations based on what Patricia Limerick calls

the "legacy of conflict" have been, until recently,

defining features of the West. Most western states have

known minimal diversity, with few African-Americans or

foreign-born immigrants. What they have had is minority

populations of Native Americans or Mexican Americans

living in clear subordination to a largely

undifferentiated white population. And western regional

mythology dwells on that relationship, celebrating the

founding dramas of conquest and repopulation with the

same callousness that the South shows in its plantation

mythology.

California has built its population and its

identity quite differently. Rapid growth and escalating

ethnic diversity are the keys. Throughout its American

history California has been a population accumulation

zone without parallel. For nearly a century and a half

the state has sustained a growth rate that essentially

doubles its population every two decades. And that has

kept the state's demography in motion. Indeed,

continuous repopulation is the critical drama of

California's history and the source of some of its

unique cultural claims. Wave after wave of newcomers

from an ever changing list of places have remade

California again and again over the years, each time

adding something new even while they allow the state to

retain its most paradoxical tradition, the tradition of

change.

While none of this resembles western regional

traits, it does accord with population processes that

the nation as a whole celebrates but which actually

occur only in a few dynamic cities and states. In this

and in many other matters California earns its right to

claim a distinction not through difference but through

emphasis. As novelist Wallace Stegner put it,

California is just like "America only more so...the

national culture at its most energetic end."

("California Rising" in Unknown California, Jonathan

Eisen, David Fine, and Kim Eisen, eds. [1985] p.8)

The state's mythology and sense of identity also

diverge from the western "conquest" model. Pioneers,

cowboys, and other conquest figures do not dominate the

symbolic landscape; indeed California's lore reads like

something of an inversion with pristine nature

idealized and a romanticized role reserved for the

Franciscan missions of pre-conquest California. The

state's self-conception descends principally from a

pair of founding myths that substantially obscure

California's own very real legacy of conquest. The

first is the gold rush, that extraordinary drama of

luck and adventure that forever fixed the state's

reputation as a land of dreams. The second derives from

the invention of Southern California in the late

nineteenth century and turns on edenic images of the

mediterranean climate, of sun, sand, and citrus, of new

healthful ways of life. All of this, to be sure, is

related to the essential western myths of the big land

and the fresh start. But California softens and

pluralizes the symbolism, moving away from images of

tough men in a rugged land, presenting itself as

gentle and therapeutic.

One thing it does share is the western emphasis on

geography. Land, climate, and location are never far

from consciousness and more readily than in other

regions suggest their powerful impact on human

habitation patterns. The incredibly varied topography

and the rich array of land use capacities have made

California both comparatively wealthy and

sociologically diverse throughout its long history of

habitation.

The state's original inhabitants, its Indian

peoples, distinguished themselves from the natives of

other parts of the continent on both points. Before

European contact California was the most densely

settled part of what is now the United States and home

to one of the greatest varieties of discrete cultures

of any place on earth. Quilted into the complex of

valleys, foothills, deserts, riverbanks, and coastal

strips were well over one hundred different tribes

speaking nearly eighty discrete languages. Only the

Mohave and Yuma of the Colorado River basin practiced

agriculture, the rest lived simply but with remarkable

stability on the foodstuffs that their small tribal

territories provided, seafood for coastal peoples like

the Chumasch, salmon for the river tribes of the North,

acorns a staple nearly everywhere.

Geography provided for early Californians in

another way, equally prefigurative. Their home was

essentially an island, surrounded by sea on one side,

barely passable mountains and deserts on the others.

For a thousand years they had been safe from the kinds

of warfare and invasions that remade tribal boundaries

in other parts of the continent. The sea protected them

too. Two centuries after most other coastal portions of

the Americas had felt the diseased and devastating

presence of Europeans, California still belonged to

Native Americans.

The Spanish visited once in 1542 during the first

great surge of European exploration and a few more

times near the close of the same century, but found

little of interest. From the standpoint of the

sixteenth century, or for that matter of the two

centuries that followed, California was one of the

remotest spots on earth, reachable only by navigating

against the winds and currents of the western Pacific.

So little did Europeans know about the place that as

late as the early 1700s it appeared on some maps as an

island.

In truth it is not geography per se but geography

in an ever-changing historical context that has shaped

California's patterns of use since that first European

contact. The region's history has been closely tied to

geo-political processes of globalization that over the

last five centuries have transformed distances,

boundaries, and civilizations. California has been

transformed and repeopled in three broad historical

phases, each distinguished by demography, culture, and

economy, each ushered in by revolutionary advances in

transportation and global political-economy. Along the

cultural and demographic axis the first period of

transformation can be labeled Hispanic, the second

period Anglo-American, the third, plural American . In

spatial notation, California began as a Pacific island,

spent its first American century becoming a region

within an Atlantic-centered nation, and the most recent

fifty years reorienting outward, westward, toward the

Pacific.

It was the second age of exploration that ended

California's privileged remoteness. For two centuries,

Spain regarded the western Pacific as its private

realm, controlling what little commerce that vast

region saw. Then in the mid-eighteenth century the

monopoly ended as English, French, and Russian ships

wandered into the area, mapping the Pacific, looking

for trading possibilities. Concerned particularly about

the string of fur-trading posts that the Russians were

establishing, Spanish authorities decided that it was

time to solidify the claim to California. A small

colonizing expedition set out from the Baja peninsula

in 1769, composed of the usual Spanish frontier

complement of soldiers, civilians, and priests, the

former to establish presidios and pueblos, the latter

to convert the Indians.

Thus began the first phase of

the repeopling of California: an eighty year period of

Mexicanization. The story is usually told in different terms,

emphasizing the Spanish flag. Independent Mexico had

charge of California only at the end, from 1821 to

1846. But the soldiers and settlers who colonized the

region were Spanish only in the limited way that George

Washington and George Rogers Clark were English when

they drove the French from the Ohio Valley. Spain

guided the settlement of California, but with only a

few exceptions the settlers were mestizos from Mexico.

More important the civilization that took shape in

those eighty years, with its unique racial amalgamation

principles, economic institutions, and cultural forms

belonged exclusively to the New World, to Mexico.

Compared to the Americans who came later, Mexicans

trod lightly on the land and peoples of California.

Spanish frontier traditions had long emphasized the

efficiencies of minimal colonization. Hispanicization

of the indigenous population rather than removal and

replacement by land hungry immigrants was the model

settlement plan. The Franciscan padres were the chief

instrument of colonization. Within thirty years they

had established a string of missions from San Diego to

San Francisco and brought the nearly 100,000 Indians

living in the coastal portions of California under

their control. Mostly it was done without the sword,

the cross and corn proving effective enough. Drawn to

the missions by the plentiful corn and beef that the

padres were soon able to produce, the Indians became

the work force for expanded levels of production,

giving up in the process not only their hunting and

gathering economy but also much of their culture and

all of their freedom. It was a poor bargain, especially

when the matter of disease is factored in. The missions

were death traps. By the early 1800s the Franciscans

were burying more Californians than they baptized and

by the end of the Mexican period the population of

coastal California had been reduced by half.

Immigration provided only a few replacements.

California's remoteness remained a major impediment to

Mexican immigration throughout the period. Nearly

impossible to reach overland because of deserts and

hostile Indians, California was tied to the Mexican

mainland by the annual visits of a single ship,

carrying news, supplies, soldier's pay, and occasional

new recruits. Spanish land use and mercantile policies

exacerbated the problem of isolation. Trade with

foreign vessels was prohibited while virtually all of

the productive land was held by the missions. With

nothing more than soldiering or subsistence farming to

attract them, immigrants arrived rarely and left almost

as frequently. When the United States seized the area

in 1846 there were fewer than 8,000 Mexican

Californians.

Dating the end of the Mexican period and the start

of Americanization is not easy. Formally California

became part of the United States in 1848, but the

American presence began long before then, and well

before the flags changed California had become

economically dependent on American ships and American

goods.

The whaling ships and trading vessels that began

to appear off the California coast in the 1820s

represented yet another stage of global reorganization,

the start of a great age of transportation improvements

that would bring vast new areas into the trading and

colonial system of the North Atlantic economies. Over

the course of the nineteenth century the far corners of

the Pacific region would gradually lose their

remoteness. Still an island in every sense but the

literal one at the start of this period, California

would by century's end be firmly bound to the American

mainland by blood, outlook, and economy.

Paradoxically Mexico's independence from Spain in

1821 opened California to American economic

penetration. Abandoning the restrictive policies that

had strangled economic activity in the province, the

new government in Mexico city allowed free access to

the ports, began the redistribution of mission lands,

and liberalized immigration procedures. This was good

news to the shoe and candle manufacturers of New

England who now provided a market for the great herds

of cattle that grazed the California hills. By the midª1830s the California economy had been completely

remade, turned from self-sufficient agriculture

controlled by the missions to a privatized ranching

economy (still based on Indian labor) geared to the

production of hides and tallow for export in Yankee

ships.

The trade brought new wealth to the province and

also new people, most notably Americans. A steady

trickle of merchants and former sailors took advantage

of lax immigration rules and settled in the coastal

pueblos, sometimes becoming ranchers, more often

providing commercial and artisanal services that were

in short supply. More ominous from the Mexican point of

view was the growing presence of Americans in the

inland valleys. Coming overland or drifting down from

Oregon, these newcomers stayed clear of the Mexican

settlements and Mexican law and built their own base of

operations in the Sacramento Valley, some of them

intending to "play the Texas game." By 1846 the Yankees

in California numbered close to 800, roughly ten

percent of the non-Indian population.

American trade and immigration after 1820 foretold

the eventual takeover of California. But the official

statements of the American government were no less

clear. Even as Mexico was securing its independence

from Spain, American ambassadors were offering to buy

California, either alone or with other parts of what

eventually became the American Southwest. The port of

San Francisco, ideal from both military and mercantile

standpoints, was of particular interest, and in 1835

Washington made another offer solely for it. These

negotiations reveal an important aspect of America's

geographic ambitions. The purpose was not necessarily

trans-continental completion. Washington was seeking a

Pacific outpost. Cognitively and geo-politically,

California remained an island, reachable only by sea,

every bit as remote as the Sandwich Islands which

shared the same trade route.

America's first off-shore acquisition came about

not through negotiation but war. California was one of

the prizes of America's first full-scale expansionist

war, fought on Mexican soil in 1846 and 1847. It was in

itself not a brutal experience for the residents of

California, who resisted valiantly but without great

loss of life. But that was merely the prelude.

Signatures had not yet been affixed to the Treaty of

Guadalupe-Hidalgo when the real act of conquest began.

The discovery of gold in early 1848 did for California

in five extraordinary years what generations could not

do in New Mexico and some other parts of the Southwest,

completely Americanize it.

The gold rush was, as John Caughey put it some

years ago, "the cornerstone," the seminal event in the

creation of American California, indeed in the whole

later history of the far west. As an economic event, it

transformed the meaning and purpose of the frontier

West. The old West, the Mississippi Valley, had been a

frontier of trappers and farmers whose slowly

developing commerce with the rest of the nation

depending on river towns and river boats. The new West

that gold-rush California introduced was not really a

frontier at all. It was a ready-made enterprise zone of

miners and ranchers followed almost immediately by

cities and railroads. There was nothing gradual about

it. As Carey McWilliams put it, for California "the

lights went on all at once." (California: The Great

Exception [1976], p.25) In 1848 California had been a

sleepy port of call on the hide and tallow trade. Two

years later, with a hundred thousand new residents and

one of the busiest ports in the world, California had

become the newest state in the United States--the only

one west of Missouri. That was just the beginning. This

instant state also claimed a sophisticated economy

based not just on mining but on a dynamic urban sector

that ultimately provided the financial and commercial

services to begin the development of the rest of the

west. And it started off with political muscle too:

within ten years Congress would be talking about

building a transcontinental railroad.

The key to all this was the state's instant

population, the real fortune that California earned in

the gold fever years. A quarter of a million newcomers

poured into California between 1848-1853, all but

obliterating the existing inhabitants. The tiny Mexican

population was numerically overwhelmed and quickly put

at an economic and cultural disadvantage. Outnumbered

twenty to one, unaccustomed to the laws, language, and

business culture that now governed their lives, they

struggled to hold onto the land and the way of life

that were guaranteed them by treaty. Within a a

generation both had been lost as courts, lawyers,

bankers, squatters, drought, and recession forced the

sale of most of the original ranchos, and as the usual

manifestations of Yankee racism and religious prejudice

undermined their cultural authority. By the 1880s, many

of the "Californios," as the pre-conquest Mexicans

called themselves, were eeking out a shabby life in the

barrios of Southern California. Poor and forgotten,

they had become strangers in their own land.

California's remaining Indian populations fared

much worse--indeed worse even than the usual horror

that attended American westward expansion. With

Congress forsaking all efforts to set up reservations,

Indian policy fell to the new settlers, who opted for

extermination. A twenty year campaign of slaughter

abetted by the spread of disease became a veritable

holocaust. Some tribes were completely eliminated,

leaving not a single survivor. Altogether in 1870

census takers could find only 17,000 Indians, just six

percent of the area's estimated original population of

300,000.

Thus began the American repopulation of

California, a process that would steadily change the

demographic mix over the years as California adopted

new roles in the global political economy. Its first

new population reflected its initial role as a place of

high adventure, attracting an international assortment

of the daring and enterprising, nearly all young males.

They came principally from places reached by the

rapidly expanding North Atlantic commerce system and

accessible to California by water. Two-thirds were

Americans, mostly from the Atlantic seaboard,

especially New York and New England. Ireland, England,

Germany, and France supplied most of the rest, but the

ports of the Pacific region also contributed:

Valparaiso, Sydney, Canton, Honolulu.

This population came to hunt gold but stayed to

build California, especially the San Francisco Bay Area

which stood ready to rechannel the acquisitive energies

of the immigrants once the placers and mines began to

play out. By 1880 the Bay Area housed forty percent of

the state's population and the city itself had more

than a quarter million residents, including, finally, a

substantial number of females. These first decades were

California's "Boston" period, a time when the

commercial and cultural commitments of New England

imprinted decisively on the new state. With merchants,

lawyers, and other New England entrepreneurs heavily

represented in the gold rush generation, California was

soon blessed with an elaborate business infrastructure

and an impressive array of manufactures to supply the

local market with everything from shoes to steamboats.

In 1854, just six years after that first cry of "gold,"

a San Francisco firm was hard at work on California's

first locomotive. The New England impress had even

more to do with culture. In Americans and the

California Dream Kevin Starr argues that the creation

of a regional culture began with the Yankee preachers

and literary lights who set out to civilize gold rush

California. Here was born the state's intellectual

infrastructure, the networks of churches and

newspapers, then schools, colleges, publishers, and

literary societies that gave the state its early

cosmopolitan aura and flare for self promotion. And

here too was born California's transcendentalist

engagement with divine nature, the key to later

reinventions of the state's identity.

Boston in the 1850s was shared by Yankees and

Irish, and so was San Francisco, which goes a long way

to explain the turbulent pattern of California politics

of the late nineteenth century. Working-class Catholic

Irish and the WASP business class faced off repeatedly

in these decades, at times with incendiary results. In

1856 a businessman's group calling itself the Committee

of Vigilance seized power, hanged several suspected

criminals and tried and deported a number of corrupt

city officials, mostly Irish. Twenty-two years later

the revolution came from the opposite quarter. Beaten

down by the mid-1870s depression and inspired by the

great railroad strike of 1877, the city's Irish and

laboring population joined Dennis Kearney's

Workingman's party and in a climate of violent

expectation elected a mayor and various other

officials, initiating a long period during which San

Francisco's working class would enjoy a measure of

political influence unparalleled in any other major

American city.

Yet there was a uniquely California aspect to this

Yankee/Irish contest. The overlapping tensions of class

and religion were mediated by a third factor, race,

that worked to the advantage of the white working

class. The Chinese were, as Alexander Saxton put it, "the indispensible enemy." Nine percent of the city's

population in 1870 and competing for laboring class

jobs, they became the focal point of late nineteenth

century working-class politics as well as the target

for riots, lynchings, and arson campaigns. The brutal

"Chinese Must Go" campaigns of the 1870s and 1880s left

several legacies, one of which was a tradition of antiªAsian politics which would last through World War II.

And the Chinese were only the first victims. Later

migrations of Japanese, Filipinos, and East Indians

would be curtailed by similar explosions of organized

hatred. "Yellow peril" politics was California's

"peculiar institution." Just as in the South, the

presence of a racial "enemy" made it possible for

whites to transcend their differences. White ethnic and

religious tensions were muted and immigrants like the

Irish would find greater economic and social

opportunities in San Francisco than in Boston in part

because of the political dynamics of race hatred.

If in its first American generation California was

a mining and urban frontier, its second incarnation was

as a farming economy, an orientation that became

practical after the completion of the first

transcontinental railroad in 1869. The event marked the

end of California's island status. Travel to eastern

population centers now took days instead of weeks or

months. More important, for the first time products

could be moved overland. The vast ocean of plains,

mountains, and deserts had finally been bridged.

The railroad turned the state into a second

Midwest, encouraging first the production of wheat,

then with the spread of irrigation and the invention of

refrigerated cars, a shift to fruits and vegetables.

While the state remained more urban than rural, by 1870

the fastest growing areas were the inland valleys where

the Central Pacific and other promoters were steering

immigrants, luring them with a campaign of cornucopic

advertising conducted extensively in heartland states

like Iowa and Illinois. By 1890 Midwesterners had

replaced North Easterners as California's principal

population group and would remain so until World War

II. Foreign immigration would continue but at a pace

that would not match the other sources of population

growth. Once forty percent of the population the

foreign-born would account for less than twenty percent

by 1930. Immigration in this period was almost entirely

from Europe and Canada, and mostly from the same

European regions that populated the Midwest: Germany,

Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia. After 1880 Italians

and Portuguese came to California in substantial

numbers but not the Eastern Europeans who in the turnªof-the-century decades were pouring into the industrial

cities of the East. Meanwhile the role of non-Europeans

was much reduced. Latin Americans and Asians had

accounted for fifteen percent of the state's population

in 1860. By 1900 they were less than seven percent and

remained at about that level through 1930s. Working

mostly in agriculture or in the tiny service sectors

that their isolated, much harrassed communities

required, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, Mexicans, and

the even smaller population of African Americans held

on precariously. Like the Midwest, California's

population was emphatically Euro-American.

Midwesternization entered a second phase around

the turn of the century with the invention of southern

California. In 1880 the six counties of southern

California claimed less than 50,000 residents, only six

percent of the state's population. By 1930 there were

2.8 million southern Californians, just about half of

the state's total. This new population magnet was built

out of orange groves, oil, tourism, real estate and a

huge dose of imagination. Railroads again opened the

way, pushing competing lines into Los Angeles in 1876

and 1885, setting off an immediate fare war and putting

both the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe into the

southern California promotion business.

Tourism was what they promoted. Southern

California was the creation of a maturing industrial

society with a growing middle class and new appetites

for leisure. The gilded age wealthy had discovered

Europe and the Grand Tour. Southern California, with

its mediterranean climate became the middle-class

alternative, especially for Midwesterners, a mere five

days away by rail. Sun and beaches, the area's natural

endowments, were only part of the appeal. As Carey

McWilliams and more recently Kevin Starr have pointed

out, southern California was an exercise in fantasy, a

barnumesque work of promotion and imagination focused

initially on the theme of mediterraneanization.

Italy, Greece, and especially Spain rose anew in

turn-of-the-century Los Angeles. Using the new building

material, stucco, developers laid out a revival

cityscape of villas, chateaus, temples, and haciendas,

creating not only fanciful hotels but entire theme

communities, the most famous of them being Abbott

Kinney's beach-side Venice, complete with canals,

imported gondoliers, and stucco recreations of

Renaissance buildings. But Spain rather than Italy

supplied the most compelling version of southern

California's mediterranean idyll. In the region's

heretofore denigrated Hispanic past, especially in the

crumbling old Franciscan missions, southern California

gained, says Starr, "the public myth which conferred

romance upon a new American region." Spanish colonial

architecture, "Old Spanish Days" parades and fiestas,

new streets and towns tagged with Spanish names, new

history lessons in the tourist magazines and school

texts--after a generation of deliberate Anglicization

of form and consciousness, California now reversed

course in a carefully constructed campaign to claim a

Spanish (but not Mexican) past.

Collaborating with the image makers was the one

grounded industry that southern California could claim

in its first period of growth. Orange growing became

another exercise in mediterranean romance, a

gentlemanly form of agriculture ideally suited to the

fantasies of inhabitants of harsher climes, farmers and

townsfolk alike. Later there would be a less glamorous

blue-collar economy with oil producing most of the

revenues, construction most of the jobs, and with a

growing branch plant manufacturing sector. But southern

California's image as a leisure frontier had been

firmly set. The gold in the second California

population rush was found in sun and oranges.

Hollywood completed the fantasy. Chasing the sun

like everyone else, the infant film industry drifted

into Los Angeles in the early years of the twentieth

century just as movies were replacing Vaudeville as the

dominant popular entertainment medium. The young city

and the young industry were a perfect match, each

thriving on artifice and invention, both products of an

era that was rapidly democratizing the pleasures of

consumerism.

Hollywood also gave California its first glimpse

of its future influence. By the 1920s the film industry

had kicked into high gear. Attracting a growing colony

of celebrities, writers, and artists, the studios

cranked out miles of celluloid to be seen weekly by

tens of millions not just in the United States but

around the world. The leading edge of the century long

project of American globalism, Hollywood's films spread

far and wide enticing images of American opulence and

equally refracted representations of California. To the

older imagery of climate, health, and wealth were added

new ones suggesting experiment and excess. Replacing

Greenwich village as the locational symbol of social

experimentalism, Los Angeles became synonymous with

sex, celebrity, hedonism, architectural and religious

oddities, and wacky politics, in short with nearly

everything new and outrageous. Film would make Los

Angeles the Peter Pan of American cities, bringing

legions of dreamers and doers who would keep the cycles

of reinvention going, making sure the city never slowed

down, that it would never grow up.

Hollywood aside, California's first American

century had been all about development and integration

into the evolving regional structures of industrial

America. American regional relations during much of

this period have often been characterized as neoªcolonial, favoring the interests of the industrial

Northeast to the detriment of the South and West. That

does not fit the California case. Its role was

definitely subordinate, but unlike the single export

economies of the South and Great Plains and the mining

and ranching states of the far west, California

supplied the nation with a range of specialized

products and services--fruits, vegetables, oil, lumber,

tourism, film--for which in most cases it was well

paid. And although the state decried the

discriminatory railroad policies and wall street

investment patterns that slanted the state's economy

away from manufacturing, a large internal market left

room for a variety of consumer manufacturers. The

result was hardly exploitative. California enjoyed one

of the highest standards of living in the nation and an

economy diverse enough to cushion many of the downturns

that battered other areas. Nevertheless California was

definitely on the periphery. Its 5.6 million people

made it the fifth largest state in 1930 but left it

very much still in the shadows. The "coast" as it was

called in eastern circles, was an amusing, distant

place known for its redwood trees, its orange groves,

and its Hollywood luminaries. Not a place anyone took

very seriously.

That would all change very shortly. World War II

initiated California's third developmental era.

Starting with an orientation that was entirely Atlantic

centered, California would turn westward, assuming much

of the responsibility for America's involvement on the

Pacific Rim. And starting as a marginal region

providing products and leisure services to core

markets, it would become a leading center of both

economic and cultural production, home to some of the

critical industries and cultural innovations of the

last half century.

The federal government was almost entirely

responsible for California's new role. Federal policy

had always to some extent privileged the state,

reflecting the nation's interest in maintaining a

credible military presence in the Pacific. A naval

shipyard in San Francisco Bay was the first substantial

federal investment in the 1850s. There would be others.

Transportation services were the major nineteenth

century target for federal funds, and California

received more than its share for harbor and river

improvements and for railroad building. Federal land

reclamation and water development projects pumped

additional millions into the state in the early decades

of the twentieth century, as did the Pacific military

buildup that began in earnest in the 1890s. By the end

of the first World War, California already possessed a

substantial military-industrial segment, including

shipyards, navy and army bases, and the beginnings of

the aircraft industry that was be so important to its

later development.

World War II turned this stream of federal funds

into a torrent. Committed to a two-ocean war,

Washington poured ten percent of its entire war budget

into California. Some of this went into building and

operating the more than one hundred military

installations that funneled men and material into the

Pacific war. Most of the rest went into war production,

giving the state a huge new industrial base. The San

Francisco Bay became the nation's shipbuilding center

while southern California turned out planes, more than

200,000 of them. Every bit as important for California

in the long run were the federal dollars spent on

scientific research, principally for the nuclear

program at the University of California and the

rocketry research at the California Institute of

Technology.

Second only to the gold rush, writes historian

Gerald Nash, the war remade California and other

western states, giving them the kind of economic

structure and population that moved them out of the

regional margins. California emerged from the war with

a highly diversified economy, perhaps the most modern

in the world. A huge military-industrial complex loaded

towards the fast-breaking aerospace and electronics

industries now complemented the increasingly efficient

agricultural economy. Added to that was a

educational/business service sector that would

develop rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s as forwardªlooking state officials invested massively in schools

and universities, building what they hoped would be the

finest public education system in the country. All

this turned California into a job creating and

population attracting machine unlike any other in the

late twentieth century. Numbers tell the story. The

1940 population of 6.9 million jumped to 15.7 million

by 1960, hit 23.7 million by 1980, and raced on past 30

million in 1990. Along the way, somewhere about 1962,

California became the nation's most populous state.

California's new economy brought also a new

demography, one befitting the increasingly global

outlook of both state and nation. The ensuing fifty

years would completely break the Midwestern pattern.

Ninety percent white in 1940, California would become

an ethnic kaleidoscope by 1990, with forty-three

percent of its population claiming Asian, African,

Latin American, or native American ancestry.

African-Americans had been only a slight presence

in California before the war, preferring the industrial

North to the unknown West during the great Southern

diaspora of the teens and twenties. But shipyard jobs

after 1942 primed the pump for a massive migration from

the western South. By 1950 California had a population

of almost 500,000 blacks which would spiral to 1.4

million by 1970. Migration slowed after that and even

reversed somewhat in the 1980s, bringing the 1990 black

population to just over 2 million or seven percent of

the state's population.

Latin-American population growth followed a

different trajectory. Beginning after the turn of the

century and helped along by the revolutionary turmoil

south of the border, Mexican immigration initially

focused mainly on farm and construction labor jobs in

southern and central California. The 1930s depression

brought that cycle to a close, but immigration

restarted in the 1940s guided mostly by urban

opportunities. Much of this was legal immigration,

since Mexicans enjoyed various loopholes and

entitlement under the immigration restriction statutes

passed in the 1920s. But an increasing percentage of

the post-war flow was undocumented. The state's largest

ethnic minority with an estimated 400,000 members in

1940, the Chicano/Latino population grew exponentially,

passing the three million mark in 1970 then exploding

in the next two decades. In the 1990 census Hispanics

numbered 7.7 million, more than one-quarter of the

state's population. Mostly Mexicans, they now also

include substantial communities from each of the

Central American countries.

The Asian story is different still. Although World

War II and its immediate aftermath removed some of the

restrictions on Asian immigration, it was not until

congress re-wrote immigration law in 1965 that the way

was cleared for the extraordinary proliferation of

peoples that in the last two decades has given new

meaning to the term diversity in California. One out of

every two legal immigrants into the United States in

this period has come from Asia and the Pacific Islands,

and more than half of them have gone to California.

This new wave is entirely different from the earlier

immigrants from China, Japan, and the Philippines who

came mostly as unskilled laborers. Often well educated

and equipped with commerical or technical skills, Asian

immigrants come now from all over the Pacific Rim, from

Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Vietnam,

Cambodia, and Laos, as well as India and Pakistan,

giving the state a combined Asian population of 2.7

million in 1990, nine percent of California's total.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the new

demography has been the repopulation of California by

native Americans, who now number almost 200,000. Some

of this can be credited to the original California

peoples whose numbers have grown steadily throughout

the twentieth century. But the largest increase has

come from outside the state, as Navaho, Lakota,

Cherokee, Choctaw and members of other nations of the

interior have followed the trail of post-war

opportunity to California.

The trail ends in Los Angeles which is to the late

twentieth-century what New York was to the century

before: a crossroads of the world, the Pacific half of

the globe in microcosm. Here spread out in the

legendary city of sprawl are the unmelted millions,

dozens of ethnicities and nationalities, no one

constituting a majority. A million African-Americans,

over three million Latin-Americans, the largest

concentration of Japanese outside Japan, of Koreans

outside Korea, and Vietnamese outside Vietnam, Chinese

from several different nations, as well as substantial

enclaves of Filipinos and South Asians. Then there are

the recent Arab, Iranian, Israeli, and Russian

immigrants. And the older ethnic communities: the

Jewish westside, the southside Okie suburbs. The story

goes on and on.

The war that opened up the new demography also

marked a fundamental change in the politics and

consciousness of California. The state had spent its

first American century unabashedly promoting poulation

growth except during depression cycles when Asians,

Latin Americans, and occasionally other groups would be

targeted for exclusion. In the last half century both

boosterism and xenophobia diminished greatly, replaced

by a less discriminatory politics of overpopulation

anxiety. Especially since the 1960s, Californians have

been more and more aware of the consequences of rapid

population growth and have answered with the toughest

environmental restrictions in the nation, though not

tough enough to resolve the mounting problems of

congestion, air pollution, water scarcity, waste

disposal and the other inevitable consequences of a

culture dedicated to escalating consumption.

The burden of racism and xenophobia has proven

only slightly less formidible. The troubled 1930s had

seen a surge of exclusionist politics, directed first

at Mexicans who were sent back across the border by the

tens of thousands in a repatriation campaign carried

out under federal auspices. Then followed a campaign

aimed ironically not at foreigners but at impoverished

American-born whites from the cotton South, the Okies

and Arkies who crossed the state border looking for

farm labor jobs. But the worst and last incident

awaited the special passions of wartime. Pearl Harbor

provided the excuse to carry out the agenda that had

many times tempted the state's powerful anti-Asian

lobby. In April 1942, with President Roosevelt's

approval, the West Coast military commander, General

John DeWitt, ordered the removal and incarceration of

the state's entire Japanese population, some 93,000

individuals, two-thirds of them citizens. Forced to

sell or abandon homes, farms, and businesses, the

internees spent most of the war in guarded, barbed-wire

enclosed camps in remote spots in the western interior.

California turned a corner in the years following

this last xenophobic exercise. After the war the state

began to dismantle its legal apparatus of caste and

exclusion. In 1948 the state's supreme court threw out

the long-enforced antimiscegenation statute and four

years later invalidated the notorious Alien land law

that kept first-generation Asian immigrants from owning

land. Meanwhile Congress and the U.S. Supreme court

abolished provisions in immigration law that prevented

Asians from becoming naturalized citizens. Two changes

were evident in these moves: the liberalizing trend

that would soon result in the broad civil rights

agendas of the late 1950s and 1960s; and a shift in the

axis of racial tension from Asian/white to black/white,

a change that brought California out of its

exceptionalist past into line with the industrial

North.

California would move through the civil rights era

more or less in line with Northern patterns, readily

abandoning de jure racial restrictions, not so readily

accepting legislation and court decisions aimed at de

facto segregation. Mandated school segregation ended in

the late 1940s, but it took another long decade of

legislative battles before the state passed in 1959 its

first law banning racial discrimination in employment.

When that was followed four years later by similar

"fair housing" legislation, the white majority

rebelled, passing a 1964 repeal initiative by a two to

one margin, only to see the courts overturn the

overturners and reinstate the anti-discrimination

measure.

Watts exploded the next summer, leaving 34 people

dead and initiating a decade and a half of desperate

conflict in the streets and courts. A rising tide of

militancy in the black and later Chicano communities

was matched by the backlash mood of many whites,

particularly when the courts in the 1970s began

ordering school boards to initiate desegregation plans.

Affirmative action programs raised further resistance.

As was the case nearly everywhere, the result was a

standoff. The old system of racial caste had been

broken but neither equality nor integration had taken

its place. The new system of inequality works on

principles of class associated with race, privileging

middle-class minorities with both occupational and

political opportunities, isolating all those who cannot

make the cut: the working poor, the dependent, the nonªEnglish speaking.

The new regime's ambiguities are heightened by the

multi-ethnic character of California society and the

uneven distribution of problems and opportunities among

the different groups. Asians, African-Americans, and

Latinos find different niches in the social order.

Blacks face the greatest economic difficulties and the

most severe social stigmas, but have developed the

greatest political resources, wielding political

influence at both state and community levels out of

proportion to their numbers. Asians are in the opposite

position: more economically successful (in the

aggregate) than other minorities, but politically

almost voiceless. Latinos fall in the middle, gaining

economic standing and slowly emerging as a political

force.

Where it all leads is anything but certain. Along

with the rest of America, California enters the 1990s

poised either to move forward into a new era of

pluralist understanding or backwards into familiar

cycles of conflict. The last few years offer portents

of both. There is on the one hand the example of the

University of California at Berkeley where the

undergraduate student population has become a showpiece

of colors and cultures and where the inevitable

tensions are muted by a nearly consensual desire to

make it work. On the other had there are the ominous

signs that Mike Davis reads in the changing polity and

cityscape of Los Angeles, where white homeowner

associations erect gated "fortress" communities, where

billions are spent on the fine arts while poverty

proliferates, where English-only ordinances and

building codes are used to fight immigrant "invasions," where industry and public officials alike retreat from

the central city, where the war on drugs turns into a

police war against a whole generation of blacks and

Latinos, where a modern metropolis veers towards the

Dickensian future foretold in Ridley Scott's film The

Blade Runner.

Some would say that the greatest reason for hope

lies in the state's transcendent cultural traditions,

in particular its capacity for innovation and change.

This notion, itself a feature of the newer, global

California, operates more on the plain of myth than

fact. It would be hard to demonstrate that Californians

in the aggregate are any more creative or attuned to

change than anyone else. It is relatively easy,

however, to show that they think they are and to

demonstrate that the state's self-image in the post-war

period increasingly involves a claim to cultural

leadership. California is "the pace setter," Carey

McWilliams told his adopted state in 1949 and

Californians have repeated it ever since, taking pride

in a whole list of supposed cultural exports, from

lifestyle innovations (hippies, hot tubs, hedonistic

Beverly Hills, gay Castro Street) to business

breakthroughs (branch banking, health maintenance

organizations, personal computers) and of course

politics (campus rebellions, environmental controls,

taxpayers revolts, and Reaganism).

Creative perhaps. More clearly the list shows the

state's capacity for social diversity and political

schizophrenia, for sustaining a range of discrete, even

antagonist, subcultures while moving erratically

between public policy agendas. It is all nicely postªmodern--the many voices, the invented personas and

plastic lifestyles, the short attention span--a

microburst cultural system capable of continuous

surprise.

Whatever its entertainment value, it is hard to

believe that mercurial California has any special gift

for solving the complex problems of pluralism let alone

the other pressing issues of a globally interdependent

age. In the end, like the nation that it aspires to

lead, California will try to get by the way it has

always gotten by, relying on its geographic gifts and

economic good fortune to feed the inflated consumer

passions of its growing and changing population, hoping

that the regime of abundance will last forever, or at

least for another generation.

--James Gregory 1993

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GENERAL WORKS

McWilliams, Carey. California: the Great Exception (1949) and Southern California: An Island on the Land (1946)

Nunis, Doyce B. and Lothrup, Gloria, eds. A Guide to the History of California (1989) the most recent bibliography

Rice, Richard B., Bullough, William A., Orsi, Richard J. The Elusive Eden: A New History of California (1988)

Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1973); Inventing the Dream: California Through the Progressive Era (1985); and Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s (1990)

BEFORE 1848

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of California 7 volumes (1884-90)

Camarillo, Albert. Chicanos in a changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California (1979)

Cook, Sherburne F. The Conflict Between the California

Indian and White Civilization (1976)

Heizer, Robert.F. and Elsasser, Albert B. The Natural World of the California Indians (1980)

Monroy, Douglas. Thrown Among Strangers: The Making of Mexican Culture in Frontier California (1990)

Weber, David J. The Mexcian Frontier: 1821-1846: The American Southwest Under Mexico (1982)

1840 TO 1940

Balderrama, Francisco E. In Defense of La Raza: The Los Angeles Mexican Consulate and the Mexican American Community, 1929 to 1936 (1982)

Caughey, John W. Gold is the Cornerstone (1948)

Fogelson, Robert M. Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930 (1967)

Gregory, James. American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (1989)

James S. Holliday. The World Rushed In: The California Gold Rush Experience (1981)

Issel, William and Cherny, Robert W. San Francisco, 1865-1932: Politics, Power, and Urban Development (1986)

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior (1975) and

China Men (1980)

Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (1987)

Lotchin, Roger. San Francisco, 1846-1856: From Hamlet to Modern City (1974)

Pisani, Donald J. From Family Farm to Aggribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California, 1850-1931 (1984)

Romo, Ricardo. East Los Angeles: History of a Barrio (1986)

Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti- Chinese Movement in California (1971)

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (1989)

RECENT PERIOD

Davis, Mike. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990)

Kotkin, Joel and Grabowicz, Paul. California, Inc. (1982)

Nash, Gerald D. The American West Transformed: The Impact of the Second World War (1985)

Walters, Dan. The New California: Facing the 21st Century (1986)

Wollenberg, Charles. All Deliberate Speed: Segregation

and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855-1975 (1976)

|