Novgorod Churches and Their Frescoes

[Return to Novgorod home page.]

Here is a start on what I hope will eventually become a much more

extensive set of pages regarding medieval Novgorod architecture and the iconography of the

interior of the churches. Photographs of the frescoes are often not readily

available, although excellent publications of single churches do exist in Russian.

There is one, for example, for the Kovalevo church. Some of the images here may not

be found elsewhere. While I provide some introductory commentary, a real analysis of

this material must wait for another time.

The two sets of images here are: 1. The Church of the Nativity

of Our Lady in the Monastery of St. Anthony; 2. The Church of the Transfiguration of

the Savior in the village of Kovalevo. Others which I shall eventually add include

the Church of the TRansfiguration of the Savior on Nereditsa and the Church of the

Transfiguration on Il'in Street. All images are thumbnailed; click to bring up the

enlargement.

The Church of the Nativity of Our Lady in the Monastery of St. Anthony

The Monastery of St. Anthony, shown on the left side of a

seventeenth-century engraving from the famous travel account by Adam Olearius, is located

north of the center of Novgorod on the East side of the Volkhov River .

According to tradition, Anthony was from Rome (hence he is called

"Rimlianin"). We know about him primarily from a Vita written late in the

fifteenth century and a sixteenth-century sermon praising him, that is, from texts written

centuries after he came to Novgorod. His Vita relates how he fled persecution of the

Orthodox by the Roman Catholic Church. Caught in a storm while on his ship, he was

saved by the miraculous appearance of a stone, on which he could stand, and when the

weather cleared, he discovered he was in Novgorod, at the location where he then founded

his monastery early in the twelfth century. He is mentioned in the Novgorod

chronicles under the years 1117 and 1147. The miraculous stone was in fact later

transported into the main church of the monastery, the Church of the Nativity, where it

was revered for its miraculous powers--a good example of popular Orthodox belief which in

many different places both in Russia and in the Orthodox East included among holy relics

stones considered to possess such powers. Miracles connected with the stone were

recorded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; the author of one of the most

interesting accounts about Muscovy, Deacon Paul of Aleppo, who visited Novgorod in 1655,

mentioned the cult of Anthony and the miraculous stone.

The Monastery of St. Anthony, shown on the left side of a

seventeenth-century engraving from the famous travel account by Adam Olearius, is located

north of the center of Novgorod on the East side of the Volkhov River .

According to tradition, Anthony was from Rome (hence he is called

"Rimlianin"). We know about him primarily from a Vita written late in the

fifteenth century and a sixteenth-century sermon praising him, that is, from texts written

centuries after he came to Novgorod. His Vita relates how he fled persecution of the

Orthodox by the Roman Catholic Church. Caught in a storm while on his ship, he was

saved by the miraculous appearance of a stone, on which he could stand, and when the

weather cleared, he discovered he was in Novgorod, at the location where he then founded

his monastery early in the twelfth century. He is mentioned in the Novgorod

chronicles under the years 1117 and 1147. The miraculous stone was in fact later

transported into the main church of the monastery, the Church of the Nativity, where it

was revered for its miraculous powers--a good example of popular Orthodox belief which in

many different places both in Russia and in the Orthodox East included among holy relics

stones considered to possess such powers. Miracles connected with the stone were

recorded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; the author of one of the most

interesting accounts about Muscovy, Deacon Paul of Aleppo, who visited Novgorod in 1655,

mentioned the cult of Anthony and the miraculous stone.

With the exception of the main church, the original buildings of the

monastery have not survived. On the left are the 19th-century gate and the refectory

Church of the presentation, built in the sixteenth century. At one time the

monastery housed the theological academy created as a result of the early

eighteenth-century church reform under Peter the Great; one of the academy buildings is

extant. Here we will concentrate on the twelfth-century Church of the Nativity of

Our Lady, a building which is arguably very important in the history of early Russian

architecture and which contains very interesting remnants of its original fresco

decoration.

With the exception of the main church, the original buildings of the

monastery have not survived. On the left are the 19th-century gate and the refectory

Church of the presentation, built in the sixteenth century. At one time the

monastery housed the theological academy created as a result of the early

eighteenth-century church reform under Peter the Great; one of the academy buildings is

extant. Here we will concentrate on the twelfth-century Church of the Nativity of

Our Lady, a building which is arguably very important in the history of early Russian

architecture and which contains very interesting remnants of its original fresco

decoration.

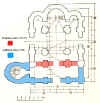

The Church of the Nativity, begun in 1117, is one of the

earliest still largely intact churches from medieval Russia. At one time, it was

thought that the structure followed the six-pillar plan common to early Orthodox churches

in the south and found in the contemporaneous Novgorod churches of St. Nicholas and St.

George (in the Iur'ev Monastery--right). Studies done as recently as two decades ago

have shown that in fact the original building had a single cupola (now it has three) and

an approximately square floor plan with only four pillars. This much was completed

by 1119, and some time after the interior had been painted in fresco in 1125, a narthex,

stairwell and balcony were added to the west end of the church, the basic construction

being completed probably prior to 1150. The current state of the building and a

floor plan delineating the addition are here:

The Church of the Nativity, begun in 1117, is one of the

earliest still largely intact churches from medieval Russia. At one time, it was

thought that the structure followed the six-pillar plan common to early Orthodox churches

in the south and found in the contemporaneous Novgorod churches of St. Nicholas and St.

George (in the Iur'ev Monastery--right). Studies done as recently as two decades ago

have shown that in fact the original building had a single cupola (now it has three) and

an approximately square floor plan with only four pillars. This much was completed

by 1119, and some time after the interior had been painted in fresco in 1125, a narthex,

stairwell and balcony were added to the west end of the church, the basic construction

being completed probably prior to 1150. The current state of the building and a

floor plan delineating the addition are here:

The importance of this relatively recent discovery about the construction

of the church lies in the fact that the three-apse, single-coupola, four-pillar church

became the norm in many parts of Russia in subsequent centuries. The argument now is

made that this form may have originated in Novgorod, possibly even with the Church of the

Nativity, and from there spread to other regions.

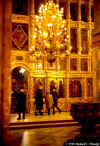

The interior of this early church also provides interesting evidence

regarding iconographic programs and displays. Today the icon screen, which separates

the eastern (altar sanctuary) end of the church from the rest, as an obligatory feature of

Orthodox churches (see photo, right). However, icon screens developed over some

time, perhaps reaching their full height and complexity only in the early fifteenth

century in Russia. In earlier centuries, the main iconographic program of a masonry

church would be displayed in the mosaics or frescoes on its walls. Individual icons

of importance might be attached to the forward pillars, placed on stands, or possibly hung

from a crossing beam in the center between the forward pillars. It is likely that

the first "icon screens" were drapes which could be pulled to close off the

sanctuary and might display a holy image.

The interior of this early church also provides interesting evidence

regarding iconographic programs and displays. Today the icon screen, which separates

the eastern (altar sanctuary) end of the church from the rest, as an obligatory feature of

Orthodox churches (see photo, right). However, icon screens developed over some

time, perhaps reaching their full height and complexity only in the early fifteenth

century in Russia. In earlier centuries, the main iconographic program of a masonry

church would be displayed in the mosaics or frescoes on its walls. Individual icons

of importance might be attached to the forward pillars, placed on stands, or possibly hung

from a crossing beam in the center between the forward pillars. It is likely that

the first "icon screens" were drapes which could be pulled to close off the

sanctuary and might display a holy image.

The Church of the Nativity dates to the period prior to the emergence of

the icon screen as we know it today. As with all early Russian churches, its

original interior was much changed over the centuries. Frescoes generally became

dark or decayed from moisture; so they were painted over, the idea being that the holy

images

were simply being renewed, not that the sanctity of the originals or the

"originality" of the early artists' work was being violated. Originality

was, after all, not a criterion in the Church art, which was the product of divinely

inspired labor. In the case of the frescoes of interest here, when the re-plastering

and re-painting were done, holes were made in the original surface in order to get the new

layer to adhere. Hence the blotchy appearance of the early frescoes when uncovered.

In the church today, one can see both some of the original frescoes and what

remains of the nineteenth century ones (especially in the cupola, left). The later

re-plastering included adding stucco decoration, which is visible in some of the

photographs. Apart from the re-painting, an icon screen was built, in the process

concealing some of the earlier frescoes and evidence about the original construction.

In the my photos taken in 1968, the remants of the blue wood of the icon screen can

be seen (right); now it has been removed entirely.

were simply being renewed, not that the sanctity of the originals or the

"originality" of the early artists' work was being violated. Originality

was, after all, not a criterion in the Church art, which was the product of divinely

inspired labor. In the case of the frescoes of interest here, when the re-plastering

and re-painting were done, holes were made in the original surface in order to get the new

layer to adhere. Hence the blotchy appearance of the early frescoes when uncovered.

In the church today, one can see both some of the original frescoes and what

remains of the nineteenth century ones (especially in the cupola, left). The later

re-plastering included adding stucco decoration, which is visible in some of the

photographs. Apart from the re-painting, an icon screen was built, in the process

concealing some of the earlier frescoes and evidence about the original construction.

In the my photos taken in 1968, the remants of the blue wood of the icon screen can

be seen (right); now it has been removed entirely.

The removal of the icon screen made it possible to establish that probably

in the original church a single beam crossed the front pillars approximately "one

storey" above the ground. From it would have been hung a curtain, but on the

front of the pillars just above and below it very sizeable icons were displayed.

There may or may not have been a group of small icons suspended from the middle section of

the beam. I have not attempted here to identify all the images remaining from the

original frescoes (in fact, that may not be possible), but will comment on selected

aspects of the iconography. We start by looking up from below toward the front

pillars and main apse of the church (the view omits the "first storey"), then

look at the images of the archangel Gabriel and Mary on the respective pillars.

The depictions of Gabriel and Mary are in fact a single iconographic image--the

Annunciation, one of the important events in the liturgical calendar portraying the moment

when the archangel appears to Mary and informs her she is to give birth to Jesus.

The early Russian churches adopted from Byzantium the practice of displaying the

Annunciation as it is here--flanking the opening to the Sanctuary. Since Byzantine

artistic norms after the iconoclast controversy forbade three-dimensional portayals of

holy figures, the Byzantine artists devised a way to combine the two dimensionality of

individual paintings with the three-dimensional space created by the architecture.

Thus the Annunciation "takes place" in three dimensional space and in a sense

invites the believer's gaze into the main apse, where the key elements of the Christian

theology would be represented in additional images and in the liturgy itself. Such

a depiction of the Annunciation likely would be found even if a church were not dedicated

to the Nativity of Our Lady, as is the case here. Additional fesccoes in the apse

area seem to have included scenes specific to the life of Mary as recorded in an

apocryphal Gospel text popular in Byzantium.

Below the Annunciation are four half-figure saints (that probably was the

way they were originally portrayed, leaving space below for a large icon to be placed on

either pillar). The images are those of SS. Cyrus, John, Florus and Laurus, who

were known for their vows of poverty. The leftmost of these images is on the left

(unfortunately somewhat blurred).

Below the Annunciation are four half-figure saints (that probably was the

way they were originally portrayed, leaving space below for a large icon to be placed on

either pillar). The images are those of SS. Cyrus, John, Florus and Laurus, who

were known for their vows of poverty. The leftmost of these images is on the left

(unfortunately somewhat blurred).

The remaining early frescoes in the main part of the church are in the

lower altar and apse area. Among the themes were the Presentation in the Temple,

the Beheading of John the Baptist and the presentation of his head to Herod, the Adoration

of the Magi (detail, left) and the Dormition. Of particular interest are the images

of Moses (lower on right) and Aaron on the pillars flanking the central opening to the

altar, emphasizing the connection of the altar with the Old Testament Temple and Ark of

the Covenant. As one can see from these images, the state of preservation is poor;

in the case of the seraph in the niche, the painting is of much later date.

The remaining early frescoes in the main part of the church are in the

lower altar and apse area. Among the themes were the Presentation in the Temple,

the Beheading of John the Baptist and the presentation of his head to Herod, the Adoration

of the Magi (detail, left) and the Dormition. Of particular interest are the images

of Moses (lower on right) and Aaron on the pillars flanking the central opening to the

altar, emphasizing the connection of the altar with the Old Testament Temple and Ark of

the Covenant. As one can see from these images, the state of preservation is poor;

in the case of the seraph in the niche, the painting is of much later date.

The style of these early frescoes is a reminder of the international contacts of

medieval Rus and Novgorod in particular. V. N. Lazarev, a noted expert on early

Russian and Byzantine painting notes their "un-Byzantine" character and connects

them with some of the contemporary Romanesque art in the West. There are numerous

other examples of the art of the West making its way to Novgorod, of course not all of

them attesting to the presence in the city of western artists. In the given

instance, Lazarev leaves open the possibility that western artists contributed to the

decoration of the main church in a monastery founded by a "Roman."

Among the interesting discoveries in the restorations of recent years have been

frescoes in the stairwell (below). Some time scholars discovered an image that

appears to be the Virgin Mary in a nimbus, holding what might have been a model of the

church, and adjoining that image to its right is the figure of a man inclined toward the

nimbus. This has been interpreted as possibly an image of the architect, presenting

his work to Mary for her blessing, although it is also possible that here we have simply a

novgorodian praying to an image of the Virgin of the Sign. The name "Foma"

is painted inside the nimbus, and letters have been scratched above the man's head.

Only recently, in the summer of 2000, another fresco was discovered in the

stairwell--an image of a lion. Lest one jump to the conclusion this is an example of

secular art in the church (not impossible, of course), it is worth remembering that carved

lions abound on the churches of the Vladimir area and tend to be interpreted in the

Christian iconography as having the power to ward off evil.

The Frescoes of the Church of the Transfiguration

of the Savior in Kovalevo.

The small church in Kovalevo, located on the Volkhovets River, was

built at the behest of a Novgorod boyar Ontsifor Zhabin in 1345; its fresco decoration in

1380 was paid for by Afanasii Stepanovich and his wife Maria. The frescoes were

relatively well preserved until World War II, when the church was destroyed. In them

Lazarev again sees evidence of non-Russian influences both thematically and stylistically,

either as a result of copying foreign (most likely Soth Slavic) models or the work of

foreign artists. It is worth remembering that only two years before Theophanes the

Greek had painted the Church of the Transfiguration on Il'in Street; the Turkish advance

through the Balkans sent a wave of "second South Slavic" influence into the

Russian principalities. One of the images (left) is that of a pillar saint, a

The small church in Kovalevo, located on the Volkhovets River, was

built at the behest of a Novgorod boyar Ontsifor Zhabin in 1345; its fresco decoration in

1380 was paid for by Afanasii Stepanovich and his wife Maria. The frescoes were

relatively well preserved until World War II, when the church was destroyed. In them

Lazarev again sees evidence of non-Russian influences both thematically and stylistically,

either as a result of copying foreign (most likely Soth Slavic) models or the work of

foreign artists. It is worth remembering that only two years before Theophanes the

Greek had painted the Church of the Transfiguration on Il'in Street; the Turkish advance

through the Balkans sent a wave of "second South Slavic" influence into the

Russian principalities. One of the images (left) is that of a pillar saint, a

whole series of which were included by Theophanes in the Church of the

Transfiguration. The renewed interest in these early ascetic church fathers in the

fourteenth century connects with the so-called Hesychast movement, which was popular,

among other places, in the Byzantine monastic center of Mt. Athos. Lazarev

hypothesizes that the artists of Kovalevo may have come from Athos. Another image of

some interest is the depiction (right) of SS. Constantine and Elena (that is, Emperor

Constantine the Great, founder of the Christian city of Constaintinople, and his mother,

who was closely connected with patronage in the Holy Land and the recovery of fragments of

the True Cross). They were among the most prominent "forerunners" of the

rulers in medieval Serbia and were often depicted in connection with the iconographic

genealogies of the Serbian kings. One other feature of the iconographiy in the

church is worth noting The tendency seems to have been to portray the saints largely

as separate images rather than in compositions that were thematically linked to one

another, as was often the case in earlier sets of frescoes (and in the work of

Theophanes). Kovalevo's art is an indication of the direction in which Novgorodian

monumental art was headed by the late fourteenth century, where the tendency was for the

artists increasingly to reproduce individual icons at the expense of monumentality and

thematic unity.

whole series of which were included by Theophanes in the Church of the

Transfiguration. The renewed interest in these early ascetic church fathers in the

fourteenth century connects with the so-called Hesychast movement, which was popular,

among other places, in the Byzantine monastic center of Mt. Athos. Lazarev

hypothesizes that the artists of Kovalevo may have come from Athos. Another image of

some interest is the depiction (right) of SS. Constantine and Elena (that is, Emperor

Constantine the Great, founder of the Christian city of Constaintinople, and his mother,

who was closely connected with patronage in the Holy Land and the recovery of fragments of

the True Cross). They were among the most prominent "forerunners" of the

rulers in medieval Serbia and were often depicted in connection with the iconographic

genealogies of the Serbian kings. One other feature of the iconographiy in the

church is worth noting The tendency seems to have been to portray the saints largely

as separate images rather than in compositions that were thematically linked to one

another, as was often the case in earlier sets of frescoes (and in the work of

Theophanes). Kovalevo's art is an indication of the direction in which Novgorodian

monumental art was headed by the late fourteenth century, where the tendency was for the

artists increasingly to reproduce individual icons at the expense of monumentality and

thematic unity.

The images shown here in color are the pieced-together originals (and in

the last three cases, reproductions made from them), the culmination of thousands of hours

of painstaking work on the fragments left after the destruction of the church. The

black and white photos are ones taken before the War. The lighting conditions when I

took the color slides were not ideal, nor was my film fast enough; so the images are not

always quite as sharp as one would like and there tends to be a color shift reflecting the

greenish flourescent lighting..

References:

- Viktor Lazarev, Old Russian Murals and Mosaics (London: Phaidon, 1966).

- V. M. Lazarev, Iskusstvo Novgoroda (Moscow-Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1947).

- N. A. Makarov, "Kamen' Antoniia Rimlianina," Novgorodskii istoricheskii

sbornik, 2(12) (1984), pp. 203-210.

- V. D. Sarab'ianov, "Novgorodskaia altarnaia pregrada domongol'skogo perioda,"

Ikonostas: Proiskhozhdenie--razvitie--simvolika. Ed. A. M. Lidov (Moscow:

Progress-Traditisiia, 2000), pp. 312-359.

- G. M. Shtender, V. M. Kovaleva, "O formirovanii drevnego arkhitekturnogo oblika

sobora Antonieva monastyria v Novgorode," Kratkie soobshcheniia Instituta

arkheologii, No. 171 (1982), pp. 54-60.

Return to Novgorod home page.

© 2000 Daniel C. Waugh. Last revised October 29, 2000.

The Monastery of St. Anthony, shown on the left side of a

seventeenth-century engraving from the famous travel account by Adam Olearius, is located

north of the center of Novgorod on the East side of the Volkhov River .

According to tradition, Anthony was from Rome (hence he is called

"Rimlianin"). We know about him primarily from a Vita written late in the

fifteenth century and a sixteenth-century sermon praising him, that is, from texts written

centuries after he came to Novgorod. His Vita relates how he fled persecution of the

Orthodox by the Roman Catholic Church. Caught in a storm while on his ship, he was

saved by the miraculous appearance of a stone, on which he could stand, and when the

weather cleared, he discovered he was in Novgorod, at the location where he then founded

his monastery early in the twelfth century. He is mentioned in the Novgorod

chronicles under the years 1117 and 1147. The miraculous stone was in fact later

transported into the main church of the monastery, the Church of the Nativity, where it

was revered for its miraculous powers--a good example of popular Orthodox belief which in

many different places both in Russia and in the Orthodox East included among holy relics

stones considered to possess such powers. Miracles connected with the stone were

recorded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; the author of one of the most

interesting accounts about Muscovy, Deacon Paul of Aleppo, who visited Novgorod in 1655,

mentioned the cult of Anthony and the miraculous stone.

The Monastery of St. Anthony, shown on the left side of a

seventeenth-century engraving from the famous travel account by Adam Olearius, is located

north of the center of Novgorod on the East side of the Volkhov River .

According to tradition, Anthony was from Rome (hence he is called

"Rimlianin"). We know about him primarily from a Vita written late in the

fifteenth century and a sixteenth-century sermon praising him, that is, from texts written

centuries after he came to Novgorod. His Vita relates how he fled persecution of the

Orthodox by the Roman Catholic Church. Caught in a storm while on his ship, he was

saved by the miraculous appearance of a stone, on which he could stand, and when the

weather cleared, he discovered he was in Novgorod, at the location where he then founded

his monastery early in the twelfth century. He is mentioned in the Novgorod

chronicles under the years 1117 and 1147. The miraculous stone was in fact later

transported into the main church of the monastery, the Church of the Nativity, where it

was revered for its miraculous powers--a good example of popular Orthodox belief which in

many different places both in Russia and in the Orthodox East included among holy relics

stones considered to possess such powers. Miracles connected with the stone were

recorded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; the author of one of the most

interesting accounts about Muscovy, Deacon Paul of Aleppo, who visited Novgorod in 1655,

mentioned the cult of Anthony and the miraculous stone.