How to evaluate analytically

Thus far, we’ve discussed two ways of evaluating designs. Critique collaboratively leverages human judgement and domain expertise and empiricism attempts to observe how well a design works with people trying to actually use your design. The third and last paradigm we’ll discuss is analytical . Methods in this paradigm try to simulate people using a design and then use design principles and expert judgement to predict likely problems.

There are many of these methods. Here are just a sample:

- Heuristic evaluation 5 5

Nielsen, J., & Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

is a collection of user interface design principles that, when applied systematically to a user interface, can identify many of the same breakdowns that a user test would identify. We’ll discuss this method here. - Walkthroughs 7 7

Polson, P. G., Lewis, C., Rieman, J., & Wharton, C. (1992). Cognitive walkthroughs: a method for theory-based evaluation of user interfaces. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies.

are methods where an expert (that would be you, novice designer), defines tasks, but rather than testing those tasks with real people, you walk through each step of the task and verify that a user would know to do the step, know how to do the step, would successfully do the step, and would understand the feedback the design provided. If you go through every step and check these four things, you’ll find all kinds of problems with a design. - Claims analysis 3 3

Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (1992). Getting around the task-artifact cycle: how to make claims and design by scenario. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS).

is a method where you define a collection of scenarios that a design is supposed to support and for each scenario, you generate a set of claims about how the design does and does not support the claims. This method is good at verifying that all of the goals you had for the design are actually met by the functionality you chose for the design. - Cognitive modeling 6 6

Olson, J. R., & Olson, G. M. (1990). The growth of cognitive modeling in human-computer interaction since GOMS. Human-Computer Interaction.

is a collection of methods that build models, sometimes computational models, of how people reason about tasks. GOMS 4 4John, B.E. and Kieras, D.E. (1996). The GOMS family of user interface analysis techniques: comparison and contrast. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI).

, for example, which stands for Goals, Operators, Methods, and Selection Rules, is a way of defining expert interactions with an interface and using the model to predict how long it would take to perform various tasks. This has been useful in trying to find ways to optimize expert behavior quite rapidly without having to conduct user testing.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss two of the most widely used methods: walkthroughs and heuristics.

Cognitive Walkthrough

The fundamental idea of a walkthrough is to think as the user would , evaluating every step of a task in an interface for usability problems. One of the more common walkthrough methods is a Cognitive Walkthrough 7 7 Polson, P. G., Lewis, C., Rieman, J., & Wharton, C. (1992). Cognitive walkthroughs: a method for theory-based evaluation of user interfaces. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies.

To perform a walkthrough, the steps are quite simple:

- Select a task to evaluate (probably a frequently performed important task that is central to the user interface’s value). Identify every individual action a user must perform to accomplish the task with the interface.

- Obtain a prototype of all of the states necessary to perform the task, showing each change. This could be anything from a low-fidelity paper prototype showing each change along a series of actions, or it might be a fully-functioning implementation.

- Develop or obtain persona of representative users of the system. You’ll use these to help speculate about user knowledge and behavior.

Then, for each step in the task you devised above, answer the following four questions:

- Will the user try to achieve the right effect? In other words, would the user even know that this is the goal they should have? If not, there’s a design flaw.

- Will the user notice that the correct action is available? If they wouldn’t notice, you have a design flaw.

- Will the user associate the correct action with the effect that the user is trying to achieve? Even if they notice that the action is available, they may not know it has the effect they want.

- If the correct action is performed, will the user see that progress is being made toward the solution of the task? In other words, is there feedback that confirms the desired effect has occurred? If not, they won’t know they’ve made progress. This is a design flaw.

By the end of this simple procedure, you’ll have found some number of missing goals, missing affordances, gulfs of execution, and gulfs of evaluation.

Here’s an example of a cognitive walkthrough in action:

Notice how systematic and granular it is. Slowly going through this checklist for every step is a powerful way to verify every detail of an interface. There are some flaws with this method. Most notably, if you choose just one persona, and that persona doesn’t adequately reflect the diversity of your users’ behavior, or you don’t use the persona to faithfully predict users’ behavior, you won’t find valid design flaws. You could spend an hour or two conducting a walkthrough, and end up either with problems that aren’t real problems, or overlooking serious issues that you believed weren’t problems.

Some researchers have addressed these flaws in persona choice by contributing more theoretically-informed persona. For example, GenderMag is similar to the cognitive walkthrough like the one above, but with four customizable persona that cover a broad spectrum of facets of software use 1 1 Burnett, M., Stumpf, S., Macbeth, J., Makri, S., Beckwith, L., Kwan, I., Peters, A., Jernigan, W. (2016). GenderMag: A method for evaluating software's gender inclusiveness. Interacting with Computers.

- A user’s motivations for using the software.

- A user’s information processing style (top-down, which is more comprehensive before acting, and bottom-up, which is more selective.)

- A user’s computer self-efficacy (their belief that they can succeed at computer tasks).

- A user’s stance toward risk-taking in software use.

- A user’s strategy for learning new technology.

If you ignore variation along these five dimensions, your design will only work for some people. By using multiple personas, and testing a task against each, you can ensure that your design is more inclusive. In fact, the authors behind GenderMag have deployed it into many software companies, finding that teams always find inclusiveness issues 2 2 Burnett, M.M., Peters, A., Hill, C., and Elarief, N. (2016). Finding gender-inclusiveness software issues with GenderMag: A field investigation. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

Here’s an example of people conducting a GenderMag walkthrough on several different interfaces. Notice how evaluators refer explicitly to the persona to make their judgements, but otherwise, they’re following the same basic procedure of a cognitive walkthrough:

You can download a helpful kit to run a GenderMag walkthrough.

Heuristic Evaluation

Here, we’ll discuss just one of these: Heuristic Evaluation 5 5 Nielsen, J., & Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

In practice, most people find the heuristics themselves much more useful than the process of applying the heuristics. This is probably because exhaustively analyzing an interface is literally exhausting. Instead, most practitioners learn these heuristics and then apply them as they design ensuring that they don’t violate the heuristics as they make design choices. This incremental approach requires much less vigilance.

Let’s get to the heuristics.

Here’s the first and most useful heuristic: user interfaces should always make visible the system status . Remember when we talked about state ? Yeah, that state should be visible. Here’s an example of visible state:

This manual car shift stick does a wonderful job showing system status: you move the stick into a new gear and not only is it visually clear, but also tactilely clear which gear the car is in. Can you think of an example of an interface that doesn’t make its state visible? You’re probably surrounded by them.

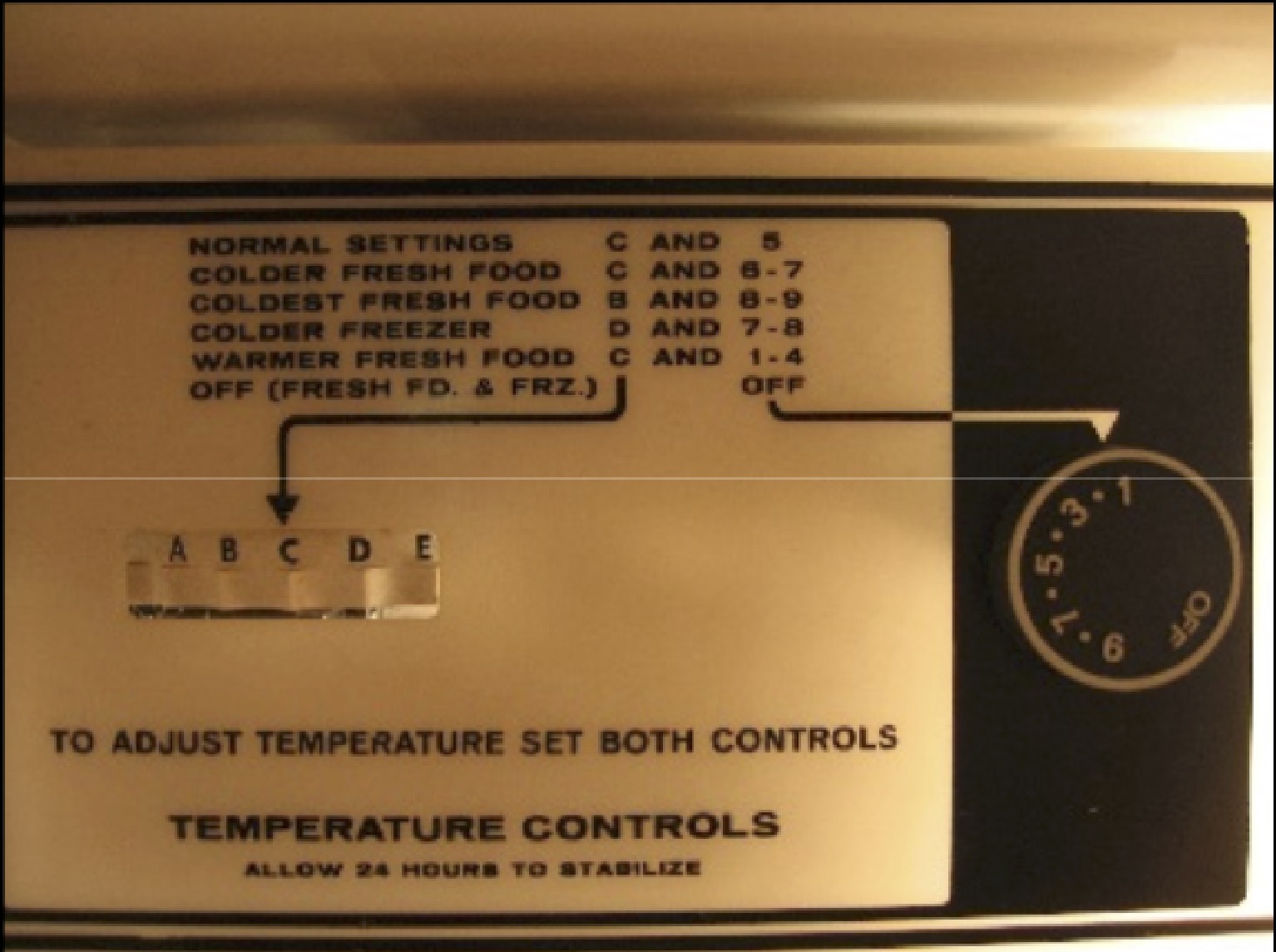

Another heuristic is real world match . The concepts, conventions, and terminology used in the system should match the concepts, conventions, and terminology that users have. Take, for example, this control for setting a freezer’s temperature:

I don’t know what kind of model you have in your head about a freezer’s temperature, but I’m guessing it’s not a letter and number based mapping between food categories. Yuck. Why not something like “cold to really cold”?

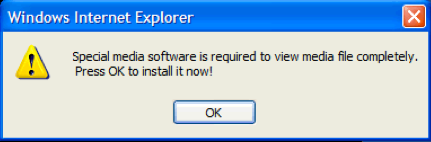

User control and freedom is the principle that people will take many paths through an interface (not always the intended ones), and so wherever they end up, they should be able to return to where they came from or change their mind. The notions of “Cancel” and “Undo” are the best examples of user control and freedom: they allow users to change their mind if they ended up in a state they didn’t want to be in. The dialog below is a major violation of this principle; it gives all of the power to the computer:

Consistency and standards is the idea that designs should minimize how many new concepts users have to learn to successfully use the interface. A good example of this is Apple’s Mac OS operating system, which almost mandates that every application support a small set of universal keyboard shortcuts, including for closing a window, closing an application, saving, printing, copying, pasting, undoing, etc. Other operating systems often leave these keyboard shortcut mappings to individual application designers, leaving users to have to relearn a new shortcut for every application.

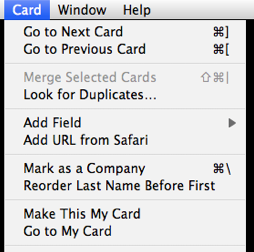

Error prevention is the idea that user interfaces, when they can, should always prevent errors rather than giving feedback that they occurred (or worse yet, just letting them happen). Here is a violation of this principle in Apple’s Contacts application that once caused me a bunch of problems:

Study this for a bit. Can you see the problem? There are two adjacent commands that do very different things. See it yet? Okay, here it is: “Go to my card” (which is a frequent command for navigating to the address book card that represents you) is right next to “Make this my card” (which is whoever you have selected in the application.) First of all, why would anyone ever want to make someone else have their identity in their address book? Second, because these are right next to each other, someone could easily change their identity to someone else. Third, when you invoke this command, there’s no feedback that it’s been done. So when I did this the first time, and browsed to a page where my browser autofilled my information into a form, suddenly it thought I was my grandma. Tracking down why took a lot of time.

Recognition versus recall is an interesting one. Recognition is the idea that users can see the options in an interface rather than having to memorize and remember them. The classic comparison for this heuristic is a menu, which allows you to recognize the command you want to invoke by displaying all possible options, versus a command line, which forces you to recall everything you could possibly type. Of course, command lines have other useful powers, but these are heuristics: they’re not always right.

Flexibility and user efficiency is the idea that common tasks should be fast to do and possible to do in many ways. Will users be saving a lot? Add a keyboard shortcut, add a button, support auto-save (better yet, eliminate the need to save, as on the web and in most OS X applications). More modern versions of this design principle connect to universal design, which tries to accommodate the diversity of user needs, abilities, and goals by offering many ways to use the functionality in an application.

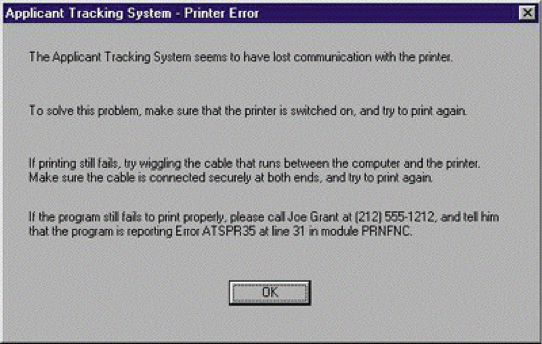

Help users diagnose and recover from errors says the obvious: if an error must happen and you can’t prevent it, offer as much help as possible to a user to help them address whatever the problem is. Here’s my favorite extreme example of this:

Of course, not every dialog needs this level of support, but you’d be surprised by just how much help is necessary. Diagnosing and recovering from errors is hard work.

I’m not fond of the last two heuristics, mostly because they’re kind of black and white. The first is offer help and documentation . This isn’t a particularly useful heuristic because its prescription is so high level. The second is minimalist design , which just seems like an arbitrary aesthetic. We’ve already discussed different notions of what makes design good . Just ignore this one.

If you can get all of these design principles into your head, along with all of the others you might encounter in this class, other classes, and any work you do in the future, you’ll have a full collection of analytical tools for judging designs on their principled merits. There’s really nothing that can substitute for the certainty of actually watching someone struggle to use your design, but these analytical approaches are quick ways to get feedback, and suitable fallbacks if working with actual people isn’t feasible.

All of these methods, while quite powerful at accelerating evaluation, make some fairly fundamental assumptions about what makes design “good”. And most of these assumptions implicitly conceive of “good” as efficient, learnable, and error-preventing. These methods do little, therefore, to assess the numerous other conceptions of design quality we have discussed, such as accessibility or justice. To evaluate those, one has to consider other methods that explicitly focus on those qualities. Moreover, all depend on you to make assumptions about people too, drawing upon persona and assumptions of common knowledge, all of which may be untrue of marginalized groups. Design has a long way to go before its methods are truly equitable, focusing on the edge cases and margins of human experience and diversity, rather than on the dominant cases. It’s your responsibility as a designer to look for those methods and demand their use.

References

-

Burnett, M., Stumpf, S., Macbeth, J., Makri, S., Beckwith, L., Kwan, I., Peters, A., Jernigan, W. (2016). GenderMag: A method for evaluating software's gender inclusiveness. Interacting with Computers.

-

Burnett, M.M., Peters, A., Hill, C., and Elarief, N. (2016). Finding gender-inclusiveness software issues with GenderMag: A field investigation. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

-

Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (1992). Getting around the task-artifact cycle: how to make claims and design by scenario. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS).

-

John, B.E. and Kieras, D.E. (1996). The GOMS family of user interface analysis techniques: comparison and contrast. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI).

-

Nielsen, J., & Molich, R. (1990). Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

-

Olson, J. R., & Olson, G. M. (1990). The growth of cognitive modeling in human-computer interaction since GOMS. Human-Computer Interaction.

-

Polson, P. G., Lewis, C., Rieman, J., & Wharton, C. (1992). Cognitive walkthroughs: a method for theory-based evaluation of user interfaces. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies.